Introduction

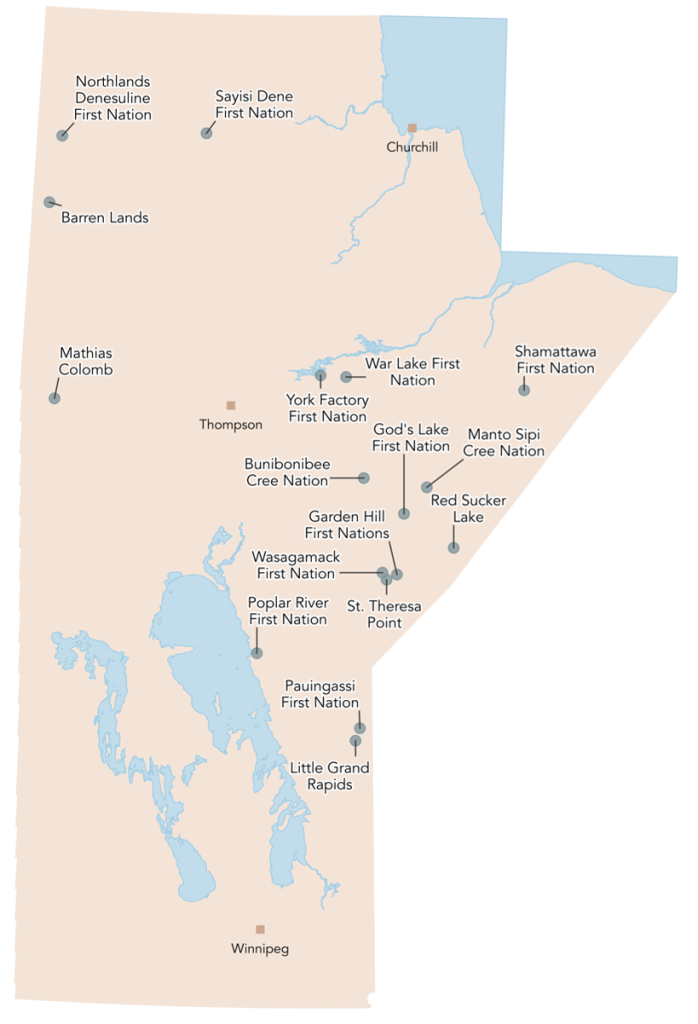

Accessing health care is a fundamental right, yet for many First Nations in Canada it remains a daily struggle shaped by geography, infrastructure, and systemic inequities. The majority of First Nations are located in rural, remote, or northern regions, where limited transportation options and underdeveloped infrastructure make routine and emergency care difficult to reach. In Manitoba, where nearly half of all First Nations are considered remote or isolated, this reality is especially stark: many communities are accessible only by air for much of the year. These barriers not only increase costs and create logistical challenges but also contribute directly to the health disparities experienced by First Nations, highlighting the urgent need for more equitable and community-led solutions.

An Issue of Isolation

First Nations in Canada are disproportionately located in rural, remote, and northern areas of the country, away from major service centres. This isolation and a deficit of transportation infrastructure makes it difficult and expensive for First Nation citizens living on-reserve to access healthcare and other essential services.

In Manitoba, this situation is especially striking as 25 of 63 First Nations are considered remote or isolated and 17 of these are not connected to an all-weather road, forcing citizens to travel in and out of the community by air for much of the year.

Non-Insured Health Benefits

When individuals are required to leave their Nation to receive medical care, they can make travel and accommodation arrangements or submit expenses for reimbursement using the Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) Non-Insured Health Benefits program (NIHB). NIHB is a product of the complicated jurisdictional framework that delineates provincial and federal responsibilities when it comes to services for First Nations. It is intended to meet the unique needs of First Nations by funding services that are not typically covered under the provincial healthcare system but to which First Nations have a treaty right. NIHB includes some dental and vision benefits, pharmaceutical coverage, and medical travel.

Each Nation has a nursing station that can provide basic care and serves as a primary point of contact to the greater healthcare system; however, there are significant limits on the scope of care that can typically be provided at these facilities and many patients must be referred elsewhere to see specialists or undergo diagnostic testing. For many, especially those with chronic conditions, this can mean travelling for routine appointments and procedures as well. Notably, obstetric care and birthing facilities are among those services which are not available in most First Nations. For several decades, an evacuation policy has been in place requiring pregnant individuals in Northern communities to relocate to a service centre with birthing facilities (usually Thompson, Winnipeg, or The Pas) between 36 and 38 weeks of gestation for the remainder of their pregnancy. Treatments such as dialysis can also necessitate an extended stay or even permanent relocation to an urban centre.

The disproportionate isolation of First Nations in Manitoba is reflected in NIHB spending. The province accounts for the highest proportion of all NIHB expenditures in the country, with medical transportation benefits composing almost half (47%) of regional spending.

Manitoba has also seen the largest net increase in medical transportation costs over recent years, an increase of $43.4 million from 2015-2020. The only region to exceed Manitoba in per-capita medical transportation spending is the North, where population density is lower and infrastructure even scarcer.

Problems with the NIHB System

Despite the expense of the travel benefit system in Manitoba, there remain serious issues and gaps. Users have reported poor communication regarding appointments and scheduling, arbitrary denials of claims, long wait and hold times, an absence of information regarding NIHB policies and processes, and experiences of racism and cultural insensitivity. The system is also fragmented with poor coordination between ISC, airlines, provincial health providers and patient accommodations. This can lead patients to miss appointments, be left without a place to say, or be stuck in the referral city longer than necessary. A lack of discharge planning and communication between specialists and local providers can also prevent patients from receiving necessary prescriptions or other follow-up care once they have returned home.

One study found that some northern medical travellers ultimately “give up” on trying to seek care rather than navigating a bureaucratic and sometimes hostile system. This can lead those disaffected by the system to avoid seeking care—an extremely concerning consequence which may contribute to First Nations experiencing higher rates of chronic conditions and worse health outcomes than other Manitobans.

Issues can also arise during patients’ stay in receiving cities. Those evacuated for births are particularly susceptible to boredom and loneliness given the prolonged length of their stays and elevated medical and emotional vulnerability. Some individuals are young, first-time parents who have never left their Nation. Others, who already have children, must leave them for an extended period and may face challenges arranging childcare. Prior to 2017, NIHB benefits did not provide for accompaniment unless the patient was a minor. Understandably, pregnant individuals facing evacuation have reported delaying access to prenatal care or intentionally missing flights to avoid facing these situations.

Improving Access and Enhancing Health Equity

Like most First Nations policy in Canada, the fragmented and bureaucratic NIHB system has its roots in the colonial history of the country. Health and social systems have not historically been designed to prioritize the wellbeing of First Nations citizens or to be accountable to them as a constituency. First Nations have long maintained that a lack of accountability and representation in decision-making remains a fundamental barrier to achieving equity for their citizens, and that to successfully address the current crisis in First Nations healthcare will require a First Nations-led transformation of health services.

Several First Nations and Tribal Councils in Manitoba have developed their own services and supports to supplement NIHB medical transformation services and improve access for their members. These include First Nations-led ground transportation services and receiving homes in cities like Winnipeg and Thompson. Similar initiatives have been established across the country as First Nations increasingly take control of their own health and social services.

Final Thoughts

Transforming the medical travel system is a crucial component of improving healthcare access and reducing disparities for northern First Nations, and there is agreement that this must be a First Nations-led process. However, transforming this system is only half the equation. Traveling should not be necessary to receive standard healthcare services and many initiatives are already underway to bring more services to First Nations whether it is through mobile medical teams or permanent in-community birthing centres.

In a transformed First Nations healthcare system, a high level of care is available in the communities where people live, and on the rare occasions when travelling for care is necessary, an efficient, patient-centred, and culturally safe medical travel system is in place to support their journey.

Share the article