Introduction

Self-governance (and what it constitutes) has been historically complex in policy, government, and inter-governmental relations. Debate persists over the operations of self-governance as a framework or system determining self-sustainability. Self-governance can be applied at varying levels and in relation to a particular organizational structure (i.e., community, Nation, or region). Of note, is how self-governance can be used in areas of Indigenous health policy, and more accurately, First Nation health system governance and local control in the Canadian context.

Defining Self-Governance

Self-governance is interwoven with democracy, specifically democratic processes such as social and political organization. Self-governance should reflect citizen-centered objectives where democracy can be exercised by equal share, direction, and ownership of institutions, laws, and political structure. Approaches to self-governance, especially from the Indigenous view, will differ depending on variables such as infrastructure, regional affiliation, government funding agreements, local government structure, and policy and/or legislation which may dictate outcomes of self-sustainability (i.e., Indian Act, the Canadian Constitution, or Treaty relations).

“Indigenous self-government is the formal structure through which Indigenous communities may control the administration of their people, land, resources and related programs and policies, through agreements with federal and provincial governments. The forms of self-government, where enacted, are diverse and self-government remains an evolving and contentious issue in Canadian law, policy, and public life.”

–William B. Henderson, 2020

A critical feature of self-governance is the departure from colonial government systems to that of a decentralized model, such as a health system under First Nation control, driven by Indigenous-centric health policy. The degrees of control for Indigenous-led health system management and health outcomes are often connected to prior implementation of federal policies and contribution agreements and are dependent on each Nation, region, and pre-existing treaty arrangements.

Self-governance, as an emerging topic of decolonial development and practice, is critical in defining what self-sustainability means for First Nations and Indigenous populations. How can self-governance in health care be achieved in a meaningful way to serve the distinct needs of First Nations? The answer is complex and requires consideration of systematic factors of colonial development as well as the current state of Western-dominant approaches of social organization, power, and regulation of institutional structures. Historically, Indigenous populations have been marginalized, restricting mobility and autonomy. In terms of self-governance, systemic inequities have been, and continue to be, enacted by informal and formal policies which replicate harmful colonial discourses and rhetoric in social and political spaces.

Any new government structure requires a host of administrative, objective-based, and democratic processes to steer decisions for the public good. Limitations are revealed when dissecting the broad strokes of government policy and administration in Canada. It has been questioned if Western standards of democracy exist in favour of the public good for Indigenous peoples. Democracy, however, is often raised as an essential feature for achieving self-governance in health or other domains.

Local democratic structures and organizations have the potential for laying a foundation for self-governance but leaves considerable room for questions in terms of the logistics of community-led development and sustainable self-government practices. Local democratic structures and health system models may face challenges due to systemic barriers. This is especially true for Indigenous populations who may seek improved community health outcomes. Indigenous populations and First Nations may aim to improve access to services such as primary care, emergency medical care, traditional medicine practice or wholistic care, and most importantly, have access to a centralized facility via self-government arrangements. However, for many First Nations, provincial and federal funding agreements, and maintenance of such services through the legacy of colonial institutions, law, and policy outcomes often prove challenging.

Indigenous Sovereignty and the Canadian State

The road to Indigenous sovereignty and self-governance in health requires rectifying Canadian legislative frameworks and Crown-Indigenous relations from an Indigenous rights-holder approach. Proposed Treaties, laws, and regulations ought to undergo evaluation directly from a First Nation or Indigenous community to identify limitations imposed by Canadian legislation. An Indigenous rights-holder approach in health self-governance helps illuminate the separation from Canadian legislative control and regulation of First Nation land, resource management, and economic mobility. Indigenous self-governance is an inherent right as claimed through section 35 of the Canadian Constitution.

“The Government of Canada recognizes the inherent right to self-government as an existing Aboriginal right under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. It recognizes, as well, that the inherent right may find expression in treaties, and in the context of the Crown’s relationship with treaty First Nations. Recognition of the inherent right is based on the view that the Aboriginal peoples of Canada have the right to govern themselves in relation to matters that are internal to their communities, integral to their unique cultures, identities, traditions, languages and institutions, and with respect to their special relationship to their land and their resources.”

–Section 35, Constitution Act, 1982

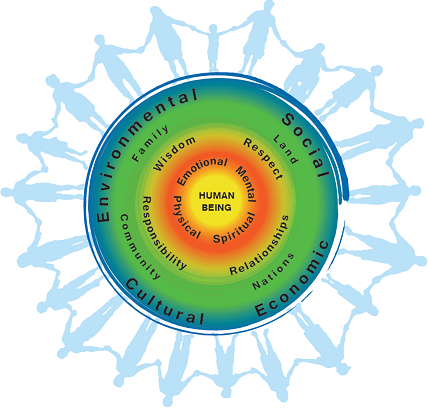

The conception and actualization of self-governance will diverge greatly for each Nation and may be conceptualized from a nation-nation, nation-community, or nation-individual sense. Indigenous self-governance in health will differ depending on varying viewpoints and what it should encompass as a framework and in practice. It may include but is not limited to, Indigenous traditional knowledge, ways of knowing and being, and inclusion of traditional medicine. There is no ‘all encompassing’ or pan-Indigenous model that fits every First Nation or Indigenous community. Each existing First Nation is as unique as the next in terms of needs, cultural identity, and traditional health practice. Self-governance for any given group will be formulated from a variation of ‘ideas’ that have been historically built depending on the Nation or group in question.

Indigenous-Led Health Care Systems

The Canadian health care system is the standard for health in Canada. Moving towards health care self-governance is a challenge due to competing systems of knowledge. There stands a general consensus that the Canadian health system is the most ‘sufficient’ or capable to address the needs of citizens at large; this system, however, largely does not consider Indigenous frameworks or approaches to health. Indigenous ways of knowing and being have often been considered as ‘alternative’ or ‘pseudo-scientific’ in the realm of health care. Conflicting worldviews, especially regarding service delivery in health, have been known to create intellectual, cultural, and political divides. Additionally, questions remain if self-governance in health care is feasible socially and economically, and if localized health care can adequately meet the needs of any given community. First Nation infrastructure varies drastically by geography, population, existing funding structures, social organization, and remoteness (i.e., proximity to a major city centre and/or health facility). However, an Indigenous-led approach holds significance politically and has the potential to carve a new path for future health system models.

Indigenous Self-Governance as a Determinant of Health

While Indigenous health and healthcare approaches have undergone a drastic shift in recent history, what is meant by ‘health’ is still shaped by Western scientific inquiry and colonial frameworks. Western-colonial practices present challenges to equitable service delivery, care, and even literacy in the realm of health care, which can be especially detrimental to diverse populations and groups that share intersecting identity characteristics (i.e., gender, ethnicity, age, race). Self-governance can arguably be considered a significant variable in assessing social determinants of health for First Nations. Social conditions and self-management are inherently connected to health equity and health status outcomes which are influenced directly by levels of income, educational attainment, and secure housing, for example.

-Jacqueline Greenblatt, 2009“The current health status among [Indigenous] people in Canada are lower than the health status of Canadians generally and has been for many decades. Much of this disparity may be attributed to differences in lifestyle, environment, social determinants and historical factors, but another factor at play may be differences in access to health care programs and services. The manners in which [Indigenous] [peoples] access health care resources, as well as the format of these resources, therefore, influence their health status.”

Historical Federal Health Self-Governance Initiatives

Relative to health status, there also stands the issue of how Indigenous self-determination in health should look.

Historical Policies Affecting Indigenous Health Outcomes in Canada:

Iterations of the 1969 White Paper, 1979 Indian Health Policy (IHP), and other similar initiatives were led with the intention to address systemic issues such as discrimination, inequality, and marginalization. However, the IHP created new issues, such as underdeveloped processes for funding, improper strategy or management of resources, and a lack of tools for securing financial alternatives separate from Health Canada. Following demand for more locally controlled health care, the Canadian Health Transfer Policy (HTP) was introduced in 1988 which fundamentally changed the character of community-led health care, development, and self-determination. Historically speaking, the HTP process did not come without issues or barriers, particularly for Indigenous peoples who were required (at least in part) to continue to collaborate with the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) and Health Canada. Community-led health was, and continues to be, confronted with jurisdictional ambiguities, gaps in health care delivery, and funding inconsistencies.

Additionally, First Nations differ greatly in terms of regional affiliation, language, knowledge distinctions, and infrastructure to support the HTP changes and implementation. With regional-distinctions, varying infrastructure, and funding support in mind, the move towards decentralized health systems, at the surface level, is a ‘positive’ outcome. In reality, the transfer of health policy may introduce difficulties for capacity building. Capacity building, (or lack thereof) in the sense of health policy transfer, could potentially result in further estrangement in health care model structures and risks associated with transfer.

For health system governance to be put into practice, it must undergo First Nation evaluation for services such as culturally appropriate care, a distinction-based approach to health for the First Nation in question, as well as to underscore the need or generalized understanding of administrative processes that go in hand with Nation-led programming and health literacy.

Conclusion

Transfer of health services to First Nations since the introduction of HTP has seen varying levels of success. However, Indigenous peoples have benefitted from regaining access, strengthening traditional and cultural lifeways, and reintroducing traditional healing practices through health care self-governance. Several initiatives of note include the Ginew Wellness Centre, (Roseau River First Nation), Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre (Lac Seul Ojibwe Nation), and Tsartlip Health Centre (Tsartlip First Nation).

Share the article