Introduction

The quality of the environment in which students learn is a crucial aspect of education. The environmental design of schools alone was found to explain 16% of the variation in primary students’ academic achievement in reading, writing, and math in United Kingdom schools in a 2017 study. Not only does the physical environment of a school impact the academic achievements of the students, but a meta-analysis conducted by the World Bank in 2019 found education infrastructure has a substantial effect on both student absenteeism, drop-out rates, and teacher retention. Other studies analyzed in the World Bank meta-analysis indicate schools can be crucial sites for community, serving citizens that are not students. This is certainly true in many First Nations where public infrastructure is limited and schools may be one of only a few local buildings where Wifi is available to the public. From a community perspective, investments in education infrastructure can have spillover benefits in the form of “skilled jobs in local communities, [the] quality of life that healthy, safe, and educationally appropriate buildings create for students and teachers, and in the benefits that quality education yields for generations to come.”

History of Education Infrastructure in Canada

The history of the education system for Indigenous students in Canada, as well as the infrastructure to facilitate such a system, can be traced back to the history of Indian Residential schools in this country. Starting in the 1800s, the Canadian government funded residential schools to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children into mainstream society. As residential schools were underfunded by the federal government, keeping costs low was a priority. By 1908, federal representatives began to note the poor conditions of many schools, including insufficient space for the number of students in both the schools and living spaces, as well as issues with the upkeep of aging buildings. As decisions regarding educational infrastructure and its funding were largely under federal jurisdiction, Canada was responsible for the poor quality of educational infrastructure, associated poor educational outcomes, and the disappearance and deaths of many Indigenous children.

Prior to the 1970s, First Nations had very little control over the choices being made on behalf of their citizens, including education and educational infrastructure. The 1970s saw a growing movement for Indigenous self-governance and sovereignty. Several Nations and Indigenous communities negotiated to regain control and discretion over their own educational systems and infrastructure. This was an invaluable step towards addressing the historical issues with the educational infrastructure; however, Nations often faced an uphill battle due to historical underfunding, paternalistic federal government policies, and the additional burden of trying to amend an educational system historically tied to the Indian Residential School system, which caused widespread intergenerational trauma and cultural destruction.

Recent Improvements to First Nations Education Infrastructure

While some First Nations have control and ownership of education facilities in their communities, funding is still partially provided by the federal government, in part due to the treaty right to education. While the federal government has historically underfunded Indigenous education, the 2016 federal budget did allocate $969.4 million, over a five-year period, starting in 2016-2017, for the construction, repair, and maintenance of First Nations education facilities. As of December 31, 2022, the federal government has spent $1.73 billion on 273 school facility projects. This is progress – however, publicly available data does not show how many requested projects for funding in that period did not receive any support.

The federal infrastructure funding process is a lengthy, confusing, and opaque; however efforts are being made to improve the process. An example is Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) is currently developing new standards for federal funding of schools. The most recent version of these standards is the 2021 School Space Accommodation Standard (SSAS) which includes more space per student, as well as outdoor learning space for land-based learning and accounts for the remoteness of the nation. However, these standards are retroactive and only apply to new projects. Combined with the lengthy review process, it has been noted the improvements currently do not do enough to address the immediate and dire infrastructure needs of many First Nations who continue to wait for education infrastructure funding.

Ongoing Underfunding and Neglect of First Nations Education Infrastructure

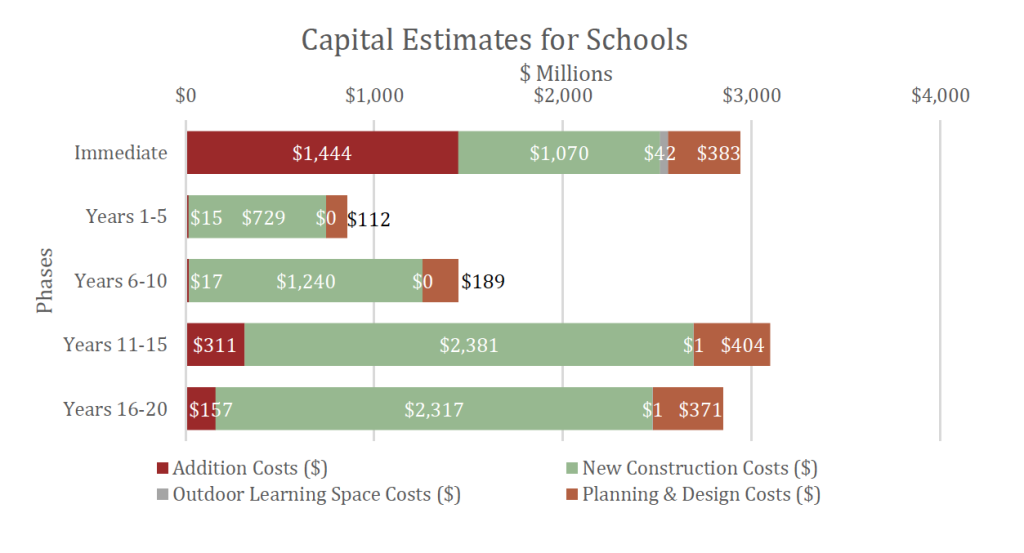

In 2021, the Assembly of First Nations published a report estimating that it would cost $11.9 billion over the next 20 years to bring all on-reserve schools across Canada up to the SSAS standards defined in 2021.

AFN also found it could cost an estimated $1.57 billion over the next 20 years to bring all on-reserve teacherages across Canada up to the Level of Service Standards and Management of Teacherages on Reserve guidelines, which are the guidelines for on-reserve teacherages in Canada.

While schools on-reserve wait for funding to rebuild or repair their educational infrastructure, infrastructure continues to age and deteriorate with use. This can have deadly consequences, such as the two school roof collapses that have happened on First Nations in Manitoba in the last three years. In March of 2020, Tataskweyak Cree Nation’s only school suffered a partial roof collapse, caused by heavy snow. The Nation has been waiting for federal funding to build two new schools to accommodate over 900 students. The school’s original capacity is 375, which was adequate for the population when it opened in 1991. In April 2023, another roof collapse occurred at the Thunderbird School in O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation in northern Manitoba. The process of building a new school had already been started but due to disagreements with the federal government over the location of the new school, the process has been delayed. Before the collapse, while the school was under repair, mould was found in the walls and asbestos was found in the tiles. Such infrastructure failings are indicative of the disrepair and hazardous conditions of too many First Nations schools in Canada.

As is indicative from the mould and asbestos found in O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation, the environmental quality of First Nations schools is a concern. For example, in 2012 the school in Berens River First Nation in Manitoba shut down when asbestos insulation was found. In 2016, Ebb and Flow First Nation, also in Manitoba, shut down their school because of concerns about exposure to dust containing asbestos that was found in the school. Along with asbestos, another concern is lead levels. A 2021 study reported thirty-five First Nations schools in British Columbia had unsafe levels of lead in their drinking water. These results were found by testing done in 2017 by the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) in 261 On-Reserve daycares and schools across First Nations in British Columbia.

Conclusion

All students deserve to learn in an environment that is safe. While historically Indigenous students have not been afforded this right to a learning environment that allows them to focus on learning and growing, the recent push led by Indigenous families, educators, and citizens is hopeful. There is still work to be done to ensure First Nations educational infrastructure is well-funded, safe, and meets the needs of the students, educators, and the Nation which the school is intended to serve.

Share the article