Introduction

Language is the keystone of culture and identity. Beyond serving to communicate, language enables the sharing of ideas, feelings, stories, and history over time and across physical space.

More than 70 distinct Indigenous languages are spoken by First Nations people across Canada. These languages hold and impart tradition, wisdom, and spirituality among their speakers but, unfortunately, use has been in steady decline, resulting from colonization, residential schools, and general cultural suppression since the arrival of Europeans.

Approximately 237,420 Indigenous people in Canada reported they could speak an Indigenous language well enough to conduct a conversation in 2021, down by 10,750, or 4.3%, from 2016.

Statistics Canada (2023)

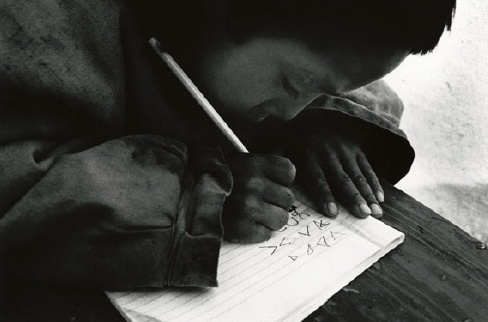

For First Nations, revitalizing and preserving language is critical to regaining and rebuilding severed cultural connections. A strong base of Indigenous language speakers fosters healthy cultural resilience and helps establish and strengthen connections between younger generations and their heritage held by Elders.

Revitalized Indigenous languages also help individuals and First Nations reclaim their voices and acknowledge the damage inflicted by colonization, such as restricting the use of Indigenous languages in residential schools. This denial of language use further suppressed and devalued Indigenous identity and culture. By sharing their stories and experiences across generations, in their ancestral languages, First Nations people can begin the process of healing and reconciliation.

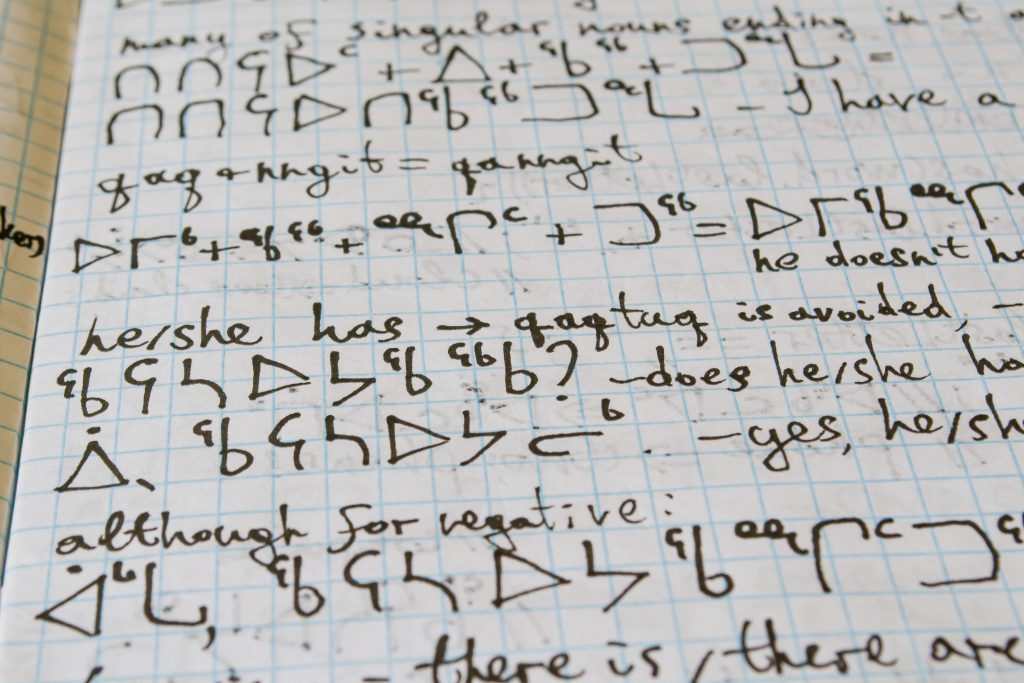

With millennia of lived experience on the land, the languages of Indigenous peoples often include extensive vocabularies linked to the world that have helped carry knowledge and wisdom forward. Revitalization of Indigenous languages, knowledge of the environment, and the collective wisdom of being stewards of the land can deepen understanding of environmental issues and sustainable practices. Beyond First Nations peoples, this connection and understanding can benefit all as Canadians must collectively deal with the impacts of pollution and climate change on the environment.

Language Revitalization Initiatives Across Canada

First Nations, non-profit organizations, and government agencies have launched various initiatives to revitalize languages. These efforts showcase the resilience and determination of Indigenous people to preserve and revive their ancestral languages, culture, and identity. Common aspects of these programs include:

- Immersing participants in the language and developing fluency through daily communication and cultural activities.

- Incorporating Elders and fluent speakers as language keepers who share their knowledge and language skills with younger generations to ensure continuity.

- Collaborating with other First Nations, universities, and government agencies to share resources and expertise in how to best revitalize Indigenous languages.

- Using technology, including online resources and language learning apps, to make language learning more accessible for those who may not be able to participate in-person or do not have easy access to fluent Elders.

These elements can help overcome the challenges of language revitalization, such as limited resources. Despite challenges, several language revitalization efforts have demonstrated ongoing successes, underscoring the determination of Indigenous peoples to preserve and revive their ancestral languages.

The Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council in British Columbia has developed language immersion programs, curriculum materials, and online resources to teach and preserve the language. Their efforts have led to increased fluency among community members. The University of Victoria offers a certificate program in Indigenous Language Revitalization that offers hands-on learning opportunities rooted in traditional knowledge and practical strategies for local language revitalization initiatives.

In Ontario, Anishinaabe communities have developed the “Ojibwe People’s Dictionary“, a searchable audio Ojibwe-English dictionary featuring the voices of Ojibwe speakers. Meanwhile, Cree communities in Quebec have language immersion programs — and community members actively use Cree in daily life and cultural events — enabled through programs such as the Cree School Board, which was established in 1978.

The Mi’kmaq Language Initiative in Atlantic Canada, which offers language courses, immersion programs, and partnerships with schools to incorporate the Mi’kmaq language in student instruction, has helped increase the number of fluent speakers. In the Yukon Territory, the Yukon Nation Language Centre provides language courses, educational materials, and collaborates with local First Nations to ensure intergenerational transmission is restored.

Language Revitalization Initiatives in Manitoba

The Manitoba Aboriginal Languages Strategy (MALS) — a partnership that includes the Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre (MFNERC), University College of the North (UCN), and Indigenous Languages of Manitoba (ILM) — provides Aboriginal language education, teacher training, the development of education programs. MALS was created to revitalize, retain, and promote seven Indigenous languages of Manitoba. Membership and representatives in MALS include Elders from each language group, representatives of leaders from the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis (FNIM) education organizations, provincial school divisions, and post-secondary institutions. By including a wide breadth of members, MALS can widely support and promote Indigenous language teaching and learning while providing resources, training, and networking opportunities for language teachers and learners.

In September 2018, the Manitoba Aboriginal Languages Strategy partnered with Red River College in Winnipeg to offer the Indigenous Language Revitalization Certificate Program. This program was designed to develop practical language competencies by helping people to read, write and speak Anishinaabemowin. The program supports individuals looking to advance language learning in education-related careers. Beyond work in education settings, the program is also useful for careers in the social services, healthcare, media, and the legal sectors where speaking Anishinaabemowin may be an asset.

Challenges Facing Language Revitalization

Language revitalization relies on a strong base of knowledgeable, fluent speakers. A central challenge facing revitalization is an ever-shrinking pool of speakers. While the integration of Elders is an important aspect of Indigenous life, the basic reality of a decreasing older population puts very real constraints on the intergenerational transfer of language and identity. With each passing year, the limits of time for older fluent speakers to pass on their knowledge are increasingly felt.

The limited number of fluent speakers is further hampered by the historical traumas inflicted on Indigenous people in residential and day schools, which took great efforts to fundamentally eradicate Indigenous languages and culture. These policies and practices also led to intergenerational gaps in fluent speakers. Rebuilding cultural pride in middle-aged and younger generations is critical to incorporating language in everyday life and cultural practices.

The daily reality of harsh economic challenges limits the resources that can be applied to language revitalization efforts in First Nations. When faced with the need to support housing, health, and education, funding language revitalization may be relegated as a future want rather than an immediate need. In this respect, explicit commitment from the federal government in recognizing and supporting language revitalization as a critical aspect of reconciliation is required in the form of dedicated funding and ongoing support.

Success in Revitalization

Success in language revitalization for First Nations in Canada depends on a strong multifaceted approach. Common aspects that contribute to successful initiatives combine:

- Community engagement, participation, and support from elders and fluent speakers who have a deep knowledge of the language and culture.

- Linguistic experts and language keepers who play a pivotal role in inter-generational transfer, particularly with children and youth.

- Integrating language in activities, ceremonies, and traditional practices to reinforce the connection between language and identity.

- Collaboration and partnership between Indigenous groups, governments, educational institutions, and non-profit organizations to provide expertise, capacity, and resources to support language programs and initiatives.

- Documentation and preservation, especially in the context of languages with limited written records, to ensure that future generations have resources for learning. Documentation can include recording oral histories, creating dictionaries, and documenting grammatical rules.

- Supportive policy and legislation, combined with long-term commitments, that can include recognizing Indigenous languages as official languages and allocate resources for language programs.

- Access to resources including adequate funding, educational materials, and technology for both instructors and learners.

Conclusion

Language revitalization for First Nations is a critical component of preserving cultural identity and supporting the resilience of individuals and First Nations in the face of ongoing challenges. While the threats to language may not be as acutely urgent as the need for safe housing, quality healthcare, or equity in education, language is a cornerstone element of long-term success in cultural preservation and reconciliation efforts for Indigenous peoples across Canada.

Share the article