Introduction

The Inuit, indigenous to the Arctic regions of what is now called Canada, Greenland, the United States, and Russia, face a unique set of hurdles that significantly impact health and well-being. For Inuit in Canada, this is a multifaceted issue that intertwines physical, social, cultural, and historical factors which cumulate to a higher incidence of mental health issues and suicide, housing insecurity, inadequate nutrition and low food security, substance use disorders, and high rates of infectious disease, such as tuberculosis.

The social determinants of Inuit health can be broadly grouped into the following categories:

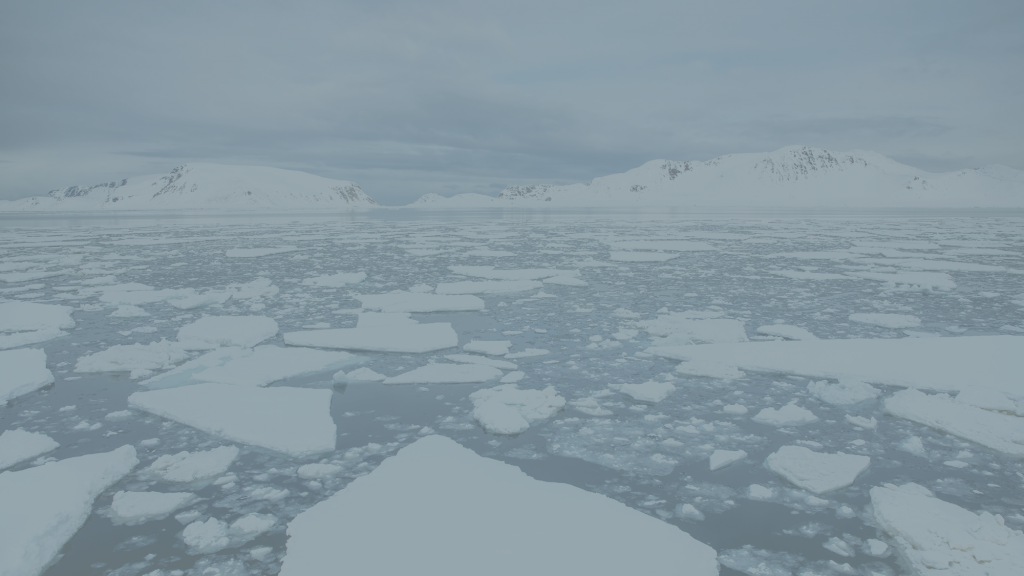

- Geography and Climate: The Arctic environment is remote and the site of extreme weather conditions that pose transportation barriers, induce a high cost of living, and limit access to healthcare services and facilities.

- Socioeconomic Factors: Economic disparity, high unemployment, poverty, and inadequate housing are prevalent in many Inuit communities. Limited access to education and employment opportunities further exacerbates vulnerability to poverty, subsequently impacting overall health and well-being.

- Historical Trauma: Inuit communities continue to experience intergenerational trauma resulting from the legacy of colonial policies, such as forced relocations and cultural assimilation. Ongoing trauma impacts mental health, evidenced in higher rates of substance use, depression, and suicide in the Inuit population.

- Cultural Disconnect: The loss of language, customs, and traditional knowledge and practices can lead to identity issues and a sense of cultural disconnect, which negatively impact mental health and well-being.

- Healthcare Accessibility: Inadequate healthcare infrastructure, shortages of healthcare professionals, the high cost of medical services, and a reliance on medical transportation to access medically necessary treatment hinders healthcare access and availability.

Inuit Healthcare Access and Transportation as Treatment

For the approximately 70,000 Inuit in Canada, most of whom live in their homeland of Inuit Nunangat, geography is a major factor affecting Inuit health. Life in the far north must contend with extreme weather conditions, transportation barriers, a high cost of living, and limited healthcare and residential infrastructure – all of which contribute to disparities in healthcare delivery and resulting health outcomes.

The north has a limited, inadequate healthcare infrastructure and resources, making healthcare delivery highly expensive and inefficient, which has resulted in the reliance on a model of medical transportation as treatment.

When patients must be transported for care, they often experience financial hardships, loneliness, emotional stress, and elevated anxiety due to removal from their physical community, traditional cultural practices, and kinship circles. For many Inuit, medical transportation also brings pronounced language isolation and often requires reliance on third-party translators (if available) or friends and family accompanying medical travel, which can incur significant costs. With so few local healthcare facilities, Inuit may be transported for a wide range of reasons including maternal care, cancer treatment, dialysis, and surgeries.

The medical transportation as treatment approach can be traced to the 1940s and the federal government’s response to the tuberculosis epidemic among Inuit populations. Inuit who were positive for tuberculosis were transported by ship to sanatoriums in southern regions of Canada. It is estimated that by 1956, approximately one out of every seven Inuit was in a sanatorium. This practice continued contrary to medical advice and comparatively lower rates in other Inuit homelands, such as Alaska, where local health aides were trained to supervise tuberculosis care in remote communities or state hospitals.

Despite recognition that community-based initiatives and telemedicine would help address the disparities in Inuit health outcomes, the policy of transportation as treatment continues unabated. As recently as the 2023 federal budget, the federal government committed to spending $810.6 million over five years “to support medical travel and to maintain medically necessary services.”

Funding is finite and each dollar spent on medical transportation is a dollar diverted from meaningful health innovations that incorporate Inuit health knowledge and develop local health facilities and capacity. Reasonable and equitable access to local universal health services can help ensure earlier diagnosis, lower mortality and comorbidity rates, all of which lead to improved physical, mental, emotional, and social outcomes. The continued reliance on medical transportation for Inuit populations is a denial of Inuit health sovereignty.

Inadequate Housing, Overcrowding, and High Rates of Tuberculosis

The federal government has acknowledged that inadequate housing is linked to a host of health problems, including increased likelihood of transmission of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and hepatitis A, and also increased risk for injuries, mental health issues, family tensions, and violence. Nearly 55% of Nunavut Inuit live in overcrowded conditions, which is considerably higher than non-Inuit populations. The combination of a harsh climate, remote locations, lack of road or rail service, underdeveloped infrastructure, and high costs of labour and materials combine to prevent the development of a healthy housing market. The creation of new housing supply in the Inuit regions is largely dependent on public sector involvement.

Tuberculosis is deeply linked to poverty and primarily affects people living in difficult socioeconomic conditions. In particular, poor housing, overcrowding in poorly ventilated spaces, and malnutrition create ideal conditions for the disease to thrive.

Tuberculosis persists at alarming rates among the Inuit. According to Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), and despite promises and funding from the federal government to reduce and eliminate tuberculosis, the rate among Inuit living in Inuit Nunangat is 300 times the national average. Tuberculosis epidemics and outbreaks are regularly present in half of the 24 communities throughout Nunavut.

Food Insecurity

Alongside extensive housing overcrowding experienced by the Inuit, food insecurity is a significant contributing factor to the health outcomes of the Inuit. Recent studies suggest that 57% of households in Nunavut experience food insecurity, almost five times the national rate of household food insecurity.

Food security is affected by the availability, quality, and accessibility of food. Northern communities experience market food supply shortages due to weather, cargo prioritization, and other factors that impact the delivery of food. When market food does arrive, it typically does not include nutritious perishables, which are prone to spoilage over long shipping distances. Additionally, the cost of market food is significantly higher in remote Inuit communities than in southern regions.

Concurrently, the Inuit have also experienced a decline in access to traditional foods and an ongoing disruption of food-sharing networks. Younger generations harvest less than previous generations, in part because of a decline in the intergenerational transfer of traditional ecological knowledge.

Food security is also affected by the ongoing impact of climate change. A rapidly changing climate has led to smaller caribou populations, changes in wildlife distribution, and increased stress on other species traditionally part of the Inuit diet. Industrialization has also led to the presence of contaminants in Arctic plants, fish, and mammals. The high cost of hunting equipment and supplies – including gas, ammunition, and vehicles – further impacts the ability to rely on traditional foods and practices, continuing to shift the population toward expensive, less-nourishing market foods.

Addressing the Challenges

The interconnected nature of the social determinants and the challenges affecting Inuit health require a multipronged approach to improving the lives of the Inuit in Canada. This includes:

- Ongoing stable investment to improve infrastructure in remote Inuit communities, including healthcare facilities and housing, will enhance access to healthcare services and lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment.

- Available healthcare practices and providers should acknowledge Inuit traditions, language, and values. Cultural competency can improve both patient communication and health outcomes.

- Engaging with Inuit communities to develop health policies and participate in decision-making can ensure that solutions consider the unique needs, history, and challenges faced by the Inuit.

Implementing these approaches while attempting to address underlying economic, educational, and employment disparities can make a positive contribution to the future health and well-being of Inuit communities.

Concluding Thoughts

Improving Inuit health requires more than temporary fixes. It demands long-term investment in housing, healthcare infrastructure, and culturally grounded approaches that respect Inuit knowledge and priorities. By centring Inuit voices in policy and ensuring access to local, equitable care, Canada can move toward addressing systemic inequities and supporting healthier futures for Inuit communities.

Share the article