Introduction

First Nations in Manitoba have a strong, historic connection to the land. However, Nations must also be understood as individually unique and diverse. Winnipeg, Manitoba, is home to the largest urban Indigenous population in Canada; yet some of the most isolated First Nations reserves in the country can be found in the province’s north. Racist depictions often treat First Nations as intrinsically tied to remote, rural settings, which does not acknowledge the forced displacement they historically endured. First Nations in Manitoba are both advocates for the natural environment as well as wanting goods, services, and supports that enable a high living standard. Provision of these goods and services, however, are limited by an isolation that was historically forced upon them by settler governments.

Background & History

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 plays an important role in mitigating the displacement of First Nations in North America, stating that settlers could not claim First Nations lands unless that land was first purchased by the Crown for sale. This also established that it was possible for land to be purchased from First Nations and the need for both parties to be present in settling treaties.

However, the Proclamation would not prevent settlers from confining First Nations to limited reserves (see the 1850 Robinson Treaties and 1850-1854 Douglas Treaties). In fact, 17th century missionaries in Sillery, New France (present day Québec City) would set aside lands for First Nations with the intention of enticing them to convert to Christianity, become sedentary, and adopt agriculture. Still, when confronted with the impending arrival of settlers and colonial domination, many First Nations leaders felt that confinement to reserves and sharing land for hunting and fishing was a preferable option.

Following Confederation in 1867 and the purchase of Rupert’s Land (including present day Manitoba) from the Hudson’s Bay Company, new policies were devised to remove First Nations and clear the land for settlers. This would include the negotiation and signing of the Numbered Treaties from 1871 to 1921. Many examples exist of the terms of the Treaties being misrepresented or narrowly interpreted to facilitate the removal of First Nations from their ancestral lands. In Manitoba Treaty 1 and 2 territory, verbal promises of access to hunting and fishing grounds were not explicitly included in the written Treaties, and were subsequently not honoured by the provincial government.

Although a cumulation of different laws since 1857, the Indian Act, 1876 was also a mechanism by which First Nations erasure could occur. Under this Act, the federal government banned ceremonies, such as the Potlatch, which was important for First Nations to convene to share food and wealth. The ban was strategic and deliberate, coinciding with a famine to facilitate the removal of First Nations to prevent impediment to the development of trans-national rail transport, integration into labour markets, and ultimately, to skirt obligations under the Numbered Treaties.

This cruel imposition on First Nations yielded a violent reaction, producing the North-West Rebellion of 1885. Anticipating unrest, the federal government instituted the Pass System, a temporary measure that remained in effect until the 1940s. The system required First Nations leaving their reserves to receive a pass from local Indian agents; without such, they faced involuntary return to their homes or incarceration. This was enforced by the North-West Mounted Police, despite the apparent illegality of confining First Nations to their reserves. The Pass System created, what some refer to as, “open air prisons” for First Nations in western Canada.

Such assimilationist policies were an effective means to remove First Nations from their traditional lands. The St. Peter’s Indian Band reserve in Manitoba (later becoming Peguis First Nation) is an example of First Nations adopting and excelling at agriculture. However, the Band was incentivized to leave for a larger, but less agriculturally-useful, plot of land. This established that reserves could not sit on suitable agricultural land if it could be occupied by white settlers. Such beliefs served as the impetus for removing First Nations from population centres and curtailing economic participation, thereby ensuring further isolation.

In some cases, the expropriation of reserve land was not about economic viability. The Soldier Settlement Board (SSB) was created in 1917 for the purposes of settling veterans of the First World War on arable land. A welfare measure of sorts, much of the SSB’s goal was to expand agribusiness and settlement through the purchase of reserve lands. This reduced the lands belonging to First Nations, in many cases land ill-suited for agriculture. Despite what the name suggests, the SSB did more to shrink reserves than to provide veterans with arable land.

The Colonial Legacy of the Reserve System

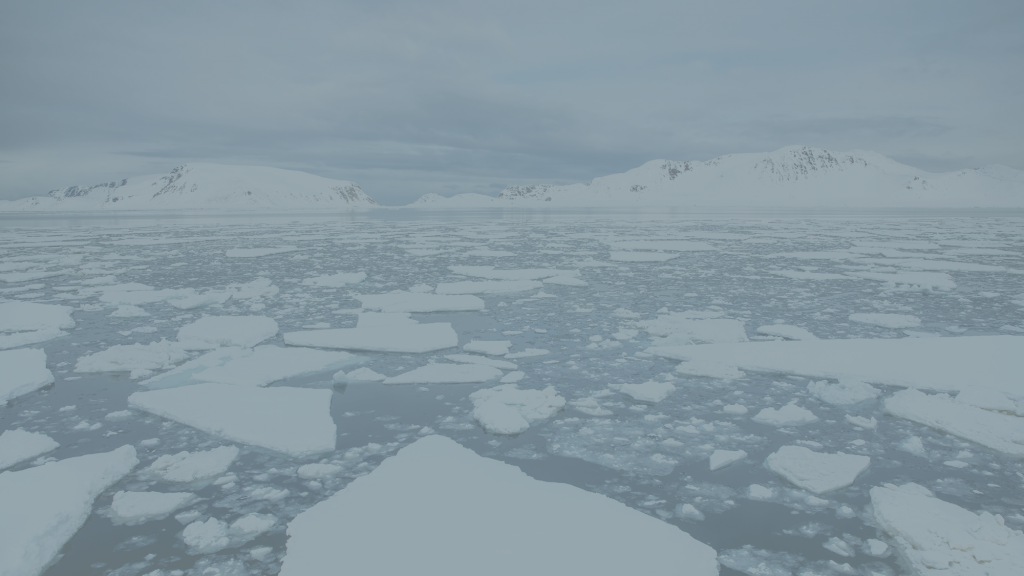

The impact of forcing First Nations to remote areas is still prominently felt in highly- isolated northern Manitoba. Educational outcomes remain comparatively poor, financial settlements still being paid out for land expropriation by the SSB, and the displacement of First Nations for the construction of hydroelectric dams and subsequent flooding continues to this day. These outcomes were not inevitable, but the product of conscious policy choices. For example, by 1990 First Nations in the United States, with a relatively comparable population to that of Canada, held a land trust 22 times larger than Canadian First Nations, dispersed across one-tenth the number of reservations. The dispersion and fragmentation of reserve lands in Canada has caused significant harm to First Nations economies, cultures, and societies.

Final Thoughts

The colonial history of Indigenous land theft suggests that more funds are needed for First Nations to ensure a quality of life comparable to that found in southern Canadian settler communities is realized. The federal government has a duty to provide goods, services, and supports regardless of how remote a reserve may be, as the higher associated costs were caused, no less, by their own policies.

Share the article