Introduction

The displacement of Indigenous Peoples from the lands they have inhabited and alienation from the Traditional Knowledge they employed for generations is not a uniquely Canadian issue. However, given the overrepresentation of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit peoples experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity in Canada – the United Nations called it a “national emergency” in 2007. The high number of Indigenous Peoples in Canada’s unhoused population represents a particularly shameful aspect of the national project. Despite being an issue that overwhelmingly affects Indigenous Peoples in Canada, there has been a consistent pattern of not providing the support nor data necessary to enact Indigenous-led change on the issue. Tied to marginalization and criminalization in the Canadian settler state, this blog examines some of the root causes and data considerations around the worsening issue of Indigenous homelessness in Canada.

Contributions to Indigenous Homelessness & Housing Insecurity

A social order that valued all community members sufficiently to house them existed pre-contact. However, displacement from ancestral lands and systemic discrimination in health and education were major contributing factors to growing rates of Indigenous homelessness. Forced relocation and assimilation via the Indian Residential School system and the broken child welfare system further deepened the issue. Decades of marginalization stemming from reduced employment opportunities, intergenerational trauma, racism, an erosion of Traditional social structures, and a school system that actively worked to “dissociate Indigenous [P]eoples from political and economic self-determination” worked in concert to create the contemporary reality of Indigenous homelessness.

Presently, ongoing jurisdictional disputes over the provision of adequate housing in the places Indigenous people have been told to call home have only exacerbated a deeply chronic, colonial-made problem. These factors have combined to build a pathway to systemically precarious housing security.

Homelessness Data in Federal Hands

The Canadian federal government – via direct and indirect various means – has allowed extractive, deficit-based, point in time data to become the norm in homelessness research and a lack of action on comprehensive, real-time, raced-based data is apparent particularly in the area of population health. Given the well-established link between health concerns such as mental wellness, addiction, substance use, family violence, and homelessness, insufficient or single day record keeping is particularly troubling. As leading American homelessness expert Roseanne Haggerty commented, “a snapshot is the wrong method… point in time count doesn’t tell you who in that population experiencing homelessness actually has a one-night problem versus a 30-year problem.”

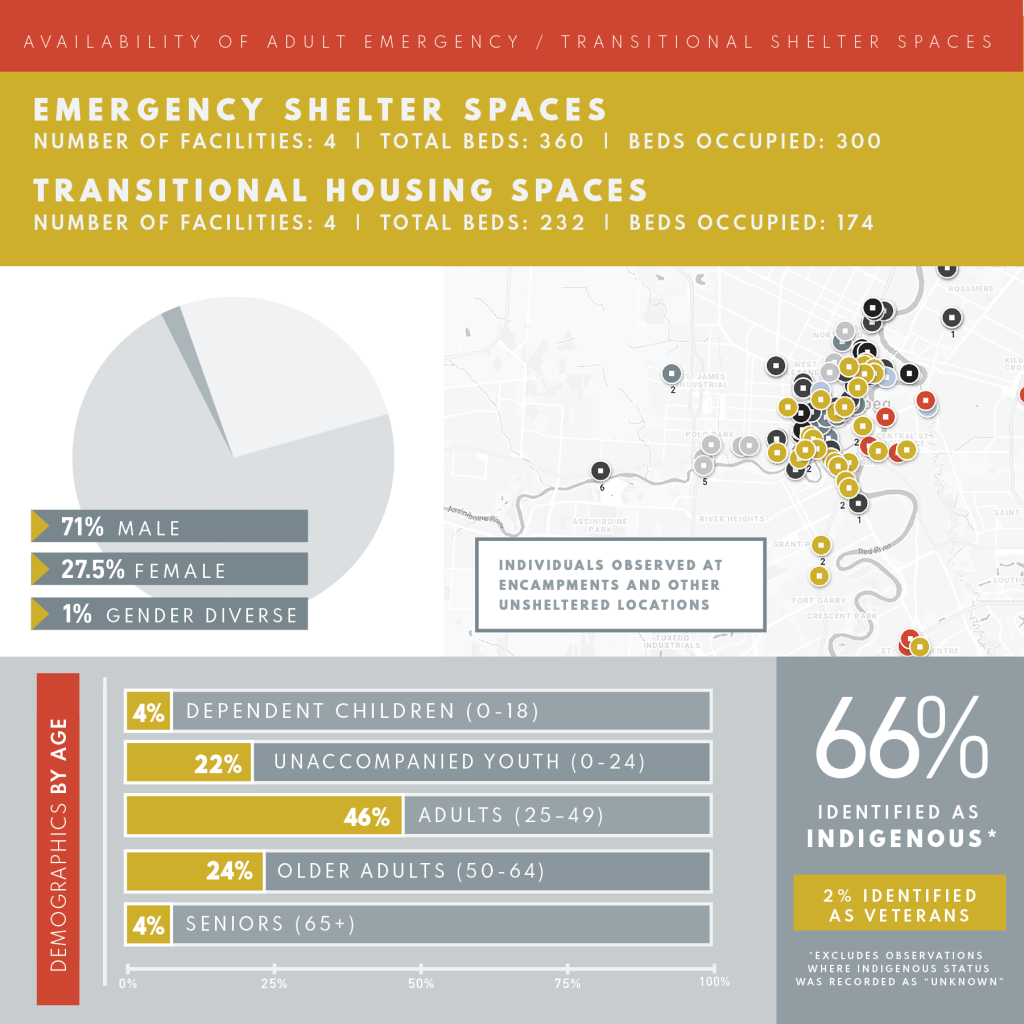

Homeless Individuals and Families Information System (HIFIS) is web-based computer software developed by the Canada Housing and Mortgage Corporation (CMHC) in the mid 1990s, passed to Employment and Social Development (ESDC) in the early 2000s, and since 2021 has been run by Infrastructure Canada (INFC) in partnership with Community Entities and shelter operators. HIFIS is a database designed to assist emergency shelter providers with daily operations such as booking in clients, maintaining bed lists, and keeping track of service providers.

A part of INFC’s Reaching Home strategy, the use of HIFIS is mandatory for Community Entities to receive federal funding, and a Data Provision Agreement with INFC must be signed to participate. The HIFIS 4.0 iteration launched in 2019 was the first networked product that could potentially allow for real-time homelessness data. However, the industry and researchers have continued to rely on project-based or point in time counts. Regional, population level, or roll-ups of data are not yet universal across Canada, despite advancements in several provinces.

Indigenous Homeless Data

Repeating the federal government’s history of paternalism – and despite a twenty-three times higher Indigenous over non-Indigenous homelessness rate – Reaching Home was not built with Indigenous input and continues to be evaluated using non-Indigenous stakeholder focus groups. Indeed, a longstanding Indigenous definition of homelessness that includes not having access to cultural supports and extends to unsafe institutional settings is also not reflected in the program.

The 2020 report, “Revisioning Coordinated Access: Fostering Indigenous Best Practices Towards a Wholistic Systems Approach to Homelessness,” authored by the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness and the Social Planning Research Council of Hamilton examined the Reaching Home program through several lenses, included that of data and data sovereignty. Of the 30 recommendations listed, five were expressly in the data sphere and are illustrative of the change required within the benchmark homelessness data collection system in Canada. These include:

- Federal homelessness benchmarks and data requirements must be co-created with Indigenous experts who can speak to the challenges particular to Indigenous people. Data collection processes need to be culturally relevant.

- Indigenous homelessness experts must contribute qualitative indicators to more accurately capture the Indigenous experience of homelessness. Feedback loops will allow for timely changes that meet community needs.

- The federal government and Indigenous homelessness experts must co-develop information material regarding data sovereignty and data governance best practice.

- Indigenous agencies have the right to influence the Reaching Home directives around data collection and use, even if this means opting out of HIFIS.

- Indigenous Community Entities working in the homelessness system must be provided with storage options that meet their needs and adequate, sustainable funding to realize their data goals.

Concluding Thoughts: Time for a New Path

Indigenous homelessness in Canada is a profound and shameful issue, reflecting the deep-seated systemic inequities rooted in colonial practices. The consistent displacement and marginalization of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit peoples, coupled with a lack of comprehensive and culturally relevant data, exacerbates this crisis. Addressing these challenges necessitates a commitment to Indigenous-led data sovereignty principles like the First Nations Principles of Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP®) or Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit to ensure that data collection and usage truly align with the needs and aspirations of Indigenous communities.

To move forward, it is imperative to co-create homelessness benchmarks and data processes with Indigenous Peoples, integrate culturally relevant qualitative indicators, and establish robust feedback mechanisms. Sustainable funding and technical infrastructure are essential to support Indigenous communities in achieving self-determined data management and governance. Only through such collaborative and respectful approaches can Canada begin to rectify the historical and ongoing injustices contributing to Indigenous homelessness and work towards equitable, effective solutions.

Share the article