Introduction

With the imposition of settler-colonialism and Western instruments of control (such as the Constitution Act, 1867 and the Indian Act, 1876), sovereign Indigenous nations in what is now known as Canada historically became beholden to colonial-hegemonic power structures under Canadian rule. For Indigenous Peoples in Canada, this framework resulted in significant social, political, and economic constraints.

Political and cultural practices within Indigenous communities underwent profound transformations, such as the suppression of traditional practices and the imposition of foreign governance models – all of which cumulated in stifled political expression and undermined cultural identities and community cohesion. By the 1960s, the call for increased accountability, transparency, and equity from all levels of government created a growing movement to counter the injustices experienced by Indigenous nations and groups. This historical context sets the stage for understanding ongoing struggles and the resilience of Indigenous activism in the face of systemic oppression in the territory known as Saskatchewan and beyond.

Colonial Rule in Saskatchewan: A Brief History

Since the 1600s, the political landscape of the Indigenous Peoples of Saskatchewan have been shaped by colonial development and European settlement. As a tactic of colonialism, the term “Indigenous” (following the earlier term “Indian”) was developed to create a broad collective obscuring the distinct identities of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Peoples. This alienated groups from their unique cultural identities and practices. The self-identified names of the First Nations in Saskatchewan include: Nêhiyawak (Plains Cree), Nahkawininiwak (Saulteaux), Nakota (Assiniboine), Dakota and Lakota (Sioux), and Denesuline (Dene/Chipewyan).

The period 1670-1870 saw the early foundations of colonial rule, which was centered around the fur trade, activities of the Hudson’s Bay Company in Rupert’s Land, and the annexation of the North-West Territories. Inland colonial expansion and the fur trade monopoly led to the transformation of the land and the lives, rights, and identities of Indigenous inhabitants. This period is marked by longstanding grievances regarding political agency and governance, and resistance against British and Canadian rule.

Transformative Events and Resistance in Saskatchewan

1850: The Robinson-Superior and Robinson-Huron Treaties – Aimed to secure land for European settlers while recognizing Indigenous rights to hunting, fishing, and gathering in designated areas. In exchange for ceding their land, Indigenous Peoples were promised annual payments and certain protections for traditional practices.

1867: Confederation of Canada – the merger of the British North American colonies of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the Province of Canada (now Ontario and Québec) marked an initial step in the nation-building process that would eventually include additional territories and provinces.

1869-70: Red River Resistance – discontent over the acquisition of Rupert’s Land emerged among the Red River Métis, who, led by Louis Riel, protested the lack of consultation and asserted their political and land rights. The Métis movement was forcibly suppressed, and some grievances were addressed through the Manitoba Act.

1871: The Crown moved to eliminate land title for First Nations and Métis Peoples in the North-West Territories and establish a settlement of First Nation reserves. Negotiation for the Numbered Treaties began with Treaty 1 and Treaty 2 territory in Lower Fort Garry.

1884-85: North-West Rebellion/Resistance – Louis Riel led the Métis in uniting discontented Indigenous populations to address grievances with the federal government. The Resistance movement issued a “Revolutionary Bill of Rights” asserting land claims and formed a Provisional Government, seizing key locations and naming Riel as president and Gabriel Dumont as military commander.

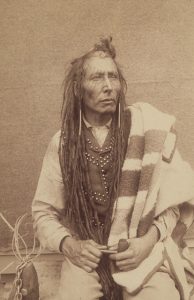

1885: Chief Poundmaker (Pihtokahanapiwiyin), a prominent Cree leader, and Chief Big Bear (Mistahimaskwa), a prominent leader of the Plains Cree, played a crucial role in the negotiation of Treaty 6 and their involvement in the North-West Resistance. Chief Poundmaker and Chief Big Bear’s legacy is one of resistance but also of diplomacy. Their efforts highlighted peace, resolution, and the honouring of Indigenous rights and agency.

1885-1996: The fallout from Resistance attempts resulted in the introduction of state-sanctioned repressive assimilation policies that violated Treaty agreements, including forced confinement to reserves, suppression of Indigenous cultures, and the heightened integration of Christian missionary Residential Schools, Indian Day Schools, and government-run Indian Hospitals and Sanatoriums.

Influential Indigenous Political Organizations in Saskatchewan: Making Historical Connections

Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN): Formerly known as the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations (FSIN), the First Nations-led organization was formed in 1946 as a response to ongoing political and social unrest aimed at Canada’s infringement on Indigenous sovereignty. Established to enhance engagement among First Nation governance and leadership, FSIN currently represents 74 First Nations in Saskatchewan and covers the designated territories of Treaty 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10. The organization embodies the cultural values and languages of the Nehiyawak (Cree), Denesuline, Saulteaux, Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota regions and communities. The FSIN plays a key role in addressing systemic issues affecting First Nations citizens, promotes economic development, and ensures that First Nations perspectives are integrated into decision-making processes at all levels of government.

Saskatchewan Indian Women’s Association (SIWA): The Saskatchewan Indian Women’s Association (SIWA), founded in the 1970s, operated independently for over 35 years. The organization aimed to address the sexist policies of the Indian Act and the government-created gender inequities for Indigenous women who lived on reserve. The goals of SIWA were to support and advance the development of Indigenous women living on reserve while coordinating the activities of First Nation organizations at the provincial level. SIWA served as a link to help First Nations women preserve and promote their culture through education, political participation, and knowledge mobilization. Closely connected with FSIN, SIWA aligned their objectives to counter similar challenges on Treaty relations, governance, and Indigenous rights through a gender-based lens.

Health-based Indigenous Activism and Self-Government

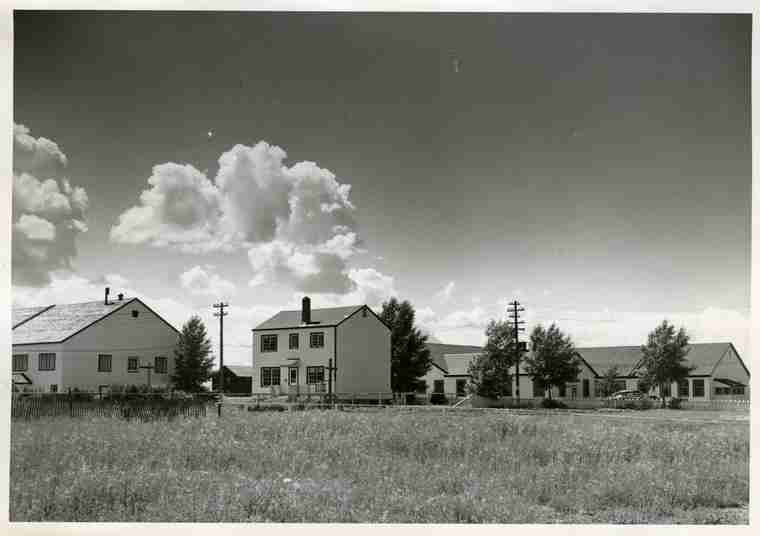

In Saskatchewan, the North Battleford Indian Hospital was established in the 1940s as part of a broader system of Indian hospitals across Canada, which were formed to segregate healthcare services for Indigenous Peoples from those available to non-Indigenous populations, reflecting the systemic inequalities of the time. Regulated by the then Department of Indian Affairs through its Indian Health Services division, “Indian hospitals” consistently faced challenges of underfunding and understaffing, as public funds were primarily allocated to non-Indigenous community hospitals.

By the 1960s, First Nation activists in Saskatchewan argued that funds meant for Indigenous healthcare should enhance Indian hospitals rather than be redirected to non-Indigenous facilities. To protest, in North Battleford First Nations organizers refused to pay provincial health taxes, claiming the Treaty 6 right to healthcare based on the Medicine Chest Clause. A local court initially upheld their claim, but the government appealed, ultimately leading to a decision that ignored the clause. By 1971, the North Battleford Indian Hospital officially closed. Part of a growing civil rights movement, the North Battleford Indian Hospital protest and growing Indigenous advocacy resulted in the federal government acknowledging its Treaty and constitutional responsibilities for Indigenous healthcare by establishing the 1979 Indian Health Policy.

Further development in Indigenous health, and specifically, the 1988 Health Transfer Policy, allowed for increased mobility, agency, and overall control of local healthcare. In recent years, an example of health self-governance in Saskatchewan is the Battle River Treaty 6 Health Centre. The first Indigenous-controlled Health Centre of its kind in Canada, the Centre is a crucial hub for Indigenous healthcare, providing culturally appropriate services that address the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual well-being of surrounding communities. Offering primary healthcare, chronic disease management, mental health support, and traditional Indigenous healing, the Centre enhances the quality of life for Indigenous Peoples in the region.

Contemporary Advancements in Self-Government in Saskatchewan

Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution affirms the Indigenous right to self-government and grants power to Indigenous communities to govern themselves according to their own laws, practices, and traditions. This right is rooted in both historical Treaties and contemporary legal frameworks, recognizing the distinct status of Indigenous Peoples within Canada.

The following is a list of contemporary self-government movements and initiatives in Saskatchewan:

- 1990: The Saskatchewan Indigenous Cultural Centre

- 1991: Saskatoon Agreement

- 1999: First Nations Land Management Act

- 2014: The First Nations Education Act

- 2017: Saskatchewan Health Authority

- 2018: The Métis Nation of Saskatchewan Governance Agreement

- 2022: The Summary Offences Procedure Amendment Act 2024: Working Together – Bilateral Agreements

As efforts to advance Reconciliation increase at all levels of government, partnership to advance self-governance in health, education, economic development, and land and wildlife management is paramount for the health, wellness, and spiritual well-being of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit peoples and communities in the province of Saskatchewan. Historical and ongoing Indigenous-led activism and advocacy has played no small part in making such advancements in self-governance a reality.

Share the article