Introduction

Indigenous Peoples’ cultural and spiritual practices, worldviews, and identities are inextricably linked with the lands and waters of their ancestral territories. Since time immemorial, intergenerational ecological knowledge of sustainable food harvesting practices enabled Indigenous people in Canada (as it is now known) to rely on traditional foods like wild meats, fish, and edible plants to satisfy all nutritional requirements.

However, centuries of colonial imposed policies have resulted in the dispossession of Indigenous Peoples’ traditional territories, restricted access to waterways, all while creating significant environmental degradation. Consequently, Indigenous people are increasingly disconnected from Indigenous food systems which promote food security and wholistic wellness, and instead resort to substituting traditional foods with less nutritious (and more expensive) commercial foods. These factors have contributed to disproportionately high rates of food insecurity among Indigenous populations in Canada.

This blog explores how ‘Indigenous food sovereignty’ initiatives could address the food insecurity faced by Indigenous communities in Canada by promoting cultural reconnection and restoring Indigenous food systems.

What is Indigenous Food Sovereignty?

The term “food sovereignty” refers to a grassroots movement that is gaining momentum around the globe with the goal of achieving long term food security. It is based on the idea that all people have the right to determine their own diet and to have access to foods that are socially, culturally, and ecologically suitable.

“Indigenous food sovereignty,” more specifically, acknowledges the complexity of Indigenous Peoples’ sacred relationships with their homelands, and is rooted in the inherent right of Indigenous people to sustain themselves by engaging in traditional land-based activities like hunting, fishing, plant harvesting, and in some territories, agriculture. In addition to increasing food security by restoring Indigenous food systems, this concept helps to preserve Traditional Knowledges, encourages (re)connection to cultural practices, and supports wholistic health.

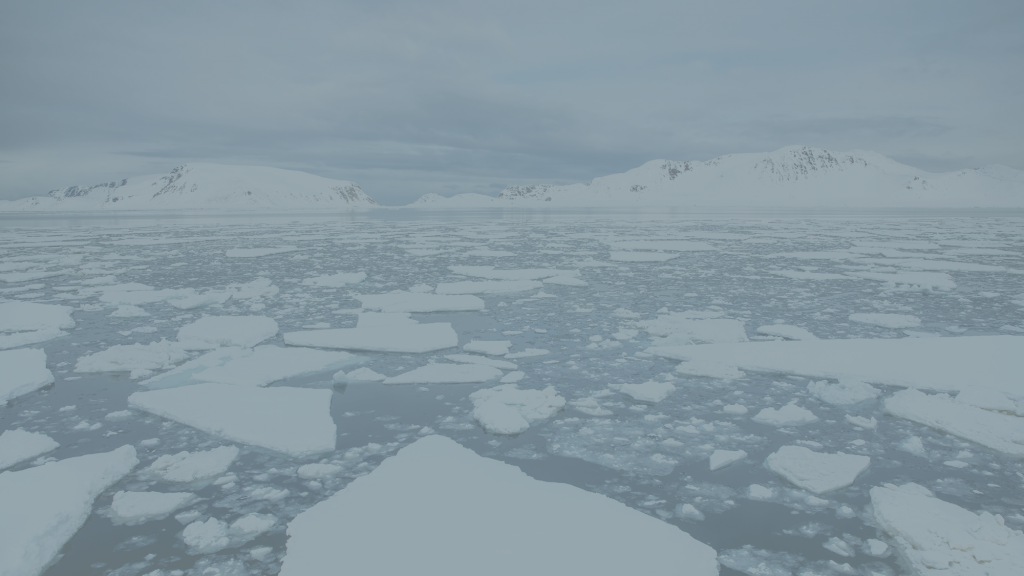

The Indigenous food sovereignty movement recognizes that the ability of communities to feed themselves with traditional foods is not only an important facet of Indigenous self-determination, but it is also vital for maintaining relationships with ancestral lands and waters, community, and the Creator.

Why are Indigenous People Disconnected from Indigenous Food Systems?

During the height of colonization in Canada, the federal government forcibly displaced many First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities from their ancestral territories to unfamiliar and often undesirable land. This process involved tactics such as violence, deception, coercion, and fraud. Some communities were relocated by distances of 2,000 kilometres, consequently disrupting the self-sufficient ways of life that Indigenous Peoples had developed over millennia of living in harmony with the environment of their homelands. Although the displacement of Indigenous Peoples was more frequent in the past, it is necessary to emphasize that displacement is a present and ongoing threat to Indigenous people, particularly as flooding and wild fires increase due to climate change.

In addition to displacement, the exploitative harvesting practices of European traders and settlers caused devastating declines in wildlife populations – most famously, the extermination of bison on the prairies – making it increasingly difficult for Indigenous people to maintain traditional food systems. By the 1800s, amid widespread malnutrition and starvation, the Canadian government began to distribute meagre food rations to some Indigenous communities. However, these rations were not only culturally inappropriate but also sometimes rancid. This era marked a nutritional turning point for Indigenous people as the “five white sins” (flour, salt, sugar, alcohol, and lard) were introduced to their diets.

Flour and lard were commonly included in the rations provided by the government. When combined with water and baked, these ingredients create bannock in its simplest form. Although many people now consider bannock to be ‘traditional’ Indigenous fare, its popularity was only gained within Indigenous communities as a survival response to colonial oppression. Therefore, bannock is viewed by some not as a symbol of tradition but of resilience.

These historical factors, combined with the devastation experienced by families and communities due to the Indian Residential School system, followed by the Sixties Scoop, and now the overinvolvement of Child and Family Services, continuously disconnect Indigenous people from traditional food systems. Indigenous food sovereignty initiatives aim to restore traditional food systems to decolonize Indigenous diets, reclaim culture, strengthen communities, and restore health.

What is Food (In)Security and How is it Related to Indigenous Health?

Being ‘food secure’ requires having, at all times, access (physical and economic) to enough food to support a healthy and active lifestyle, and to have dietary needs and preferences met. In many Indigenous communities in Canada, there is a critical lack of access to foods that are both nutritious and affordable for the average person. Many of the commercial foods that are available in-store in areas where Indigenous people tend to live (such as in First Nations, in remote or Northern communities, and in inner cities) are highly processed, low in nutritional value, unaffordable, and can be vulnerable to supply chain disruptions. These structural factors have created disproportionately high rates of food insecurity among Indigenous people.

“Cultural connectedness and the health and well-being of First Nations are deeply intertwined with their food systems, it is critical for First Nations to reclaim their food sovereignty. Indeed, restoring, maintaining, and protecting Indigenous food systems is, for First Nations, foundational to preserving their culture and improving their health and well-being.”

-Roseanne Blanchet et al. (2021)

Food insecurity can impact the health of Indigenous people by aggravating nutrition-related chronic diseases such as diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, and heart disease. This is of particular concern as Indigenous people are diagnosed with such diseases at rates significantly higher than non-Indigenous populations. For example, the prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes (T2DM) among First Nations individuals living on-reserve is more than three times that of non-Indigenous populations. However, this Canadian study showed that incorporating even small amounts of traditional foods throughout the day significantly improved the total nutritional value of one’s daily food intake for First Nations individuals, which could contribute to narrowing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous health outcomes.

Although access to enough nutritious food is a determinant of health for all people, for Indigenous people specifically, consuming traditional foods and engaging in traditional harvesting practices is additionally recognized as an important determinant of health. Studies conducted in Canada, the United States, and Australia, alongside many others, show that engaging in traditional cultural practices contributes positively to Indigenous people’s wholistic health. Many of the physical health, mental health, and socioeconomic challenges that Indigenous people experience at disproportionately high rates can be linked to the reduction in cultural connectedness that has resulted from colonization, an issue which Indigenous food sovereignty initiatives seek to address wholistically.

Conclusion

To see how Indigenous food sovereignty works in practice, initiatives happening in the following Indigenous communities across Canada are of note:

- Syilx Okanagan First Nations in British Columbia (Sockeye Salmon Reintroduction to Skaha Lake Project)

- Pimicikamak Cree Nation in Manitoba (Pimicikamak Traditional Food Scan)

- Inuit in Inuit Nunangat (Inuit Nunangat Food Security Strategy)

- O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation in Manitoba (Ithinto Mechisowin food program)

- L’sɨtkuk First Nation in Nova Scotia (Mi’kmaq concept of Netukulimk)

Indigenous food sovereignty is a multifaceted approach, aiming to enhance wholistic health and wellbeing by making nutritious traditional foods more accessible, reducing reliance on less healthy alternatives, and encouraging an active lifestyle. Additionally, engaging in traditional food harvesting practices strengthens connections to traditional territories, culture, and community, thereby supporting mental, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing. Importantly, Indigenous food sovereignty also promotes self-determination and reduces vulnerability to external factors such as supply chain disruptions and rising food costs.

Share the article