Introduction

“Canada and the world face a triple crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. Dealing with these interlocking issues requires deep collaboration, and Indigenous partnerships are crucial.”

-Mr. Steven Guilbeault, Minister of Environment and Climate Change

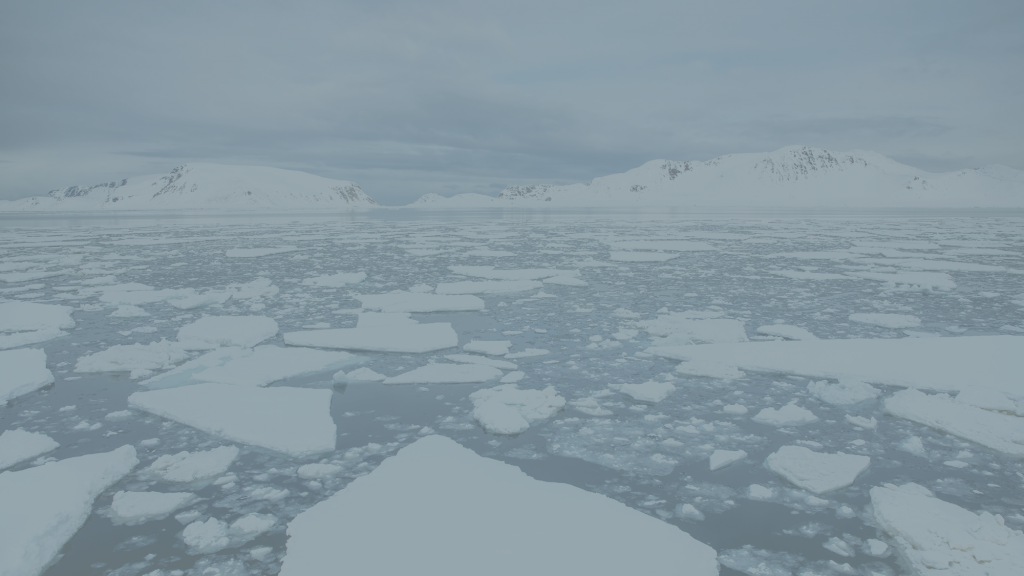

Since time immemorial, Indigenous Peoples have emphasized the importance of living in balance with the land, the environment, and its resources. Climate change is disrupting this balance. Sea levels have risen by 4.1 inches since 1992. The global temperature has increased by 1.4 °C since the preindustrial period.

Indigenous communities in Canada are experiencing the impact of global climate change in their everyday lives as sea ice recedes in the Arctic at an alarming pace, and natural disaster events, such as flooding and wildfires, occur at astonishing levels of scope and destruction. Indigenous peoples are among the first to face the direct consequences of climate change due to their dependence upon and close relationship with the land and its resources. This blog examines the impact of climate change on First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples in Canada, noting key initiatives and calls to action.

Impacts of Climate Change

Climate change can be seen across Canada in higher temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and extreme weather events such as floods and heat waves. In December 2023, Manitoba experienced the warmest December since 1970. Human-caused climate change fueled heat waves across Canada in August 2024. The Inuvik region (Northwest Territories) experienced a peak daily temperature of 26.5 °C between August 6-10, 2024 – 13 °C above normal daily high temperatures. Comparable highs, in the double digits above the average daily high temperatures, were similarly experienced in the Kivalliq and Kitikmeot regions of Nunavut during the same period.

Prolonged heat waves are a significant contributor to more intense wildfires. The 2023 wildfires in Canada burned almost 15 million hectares of forest, costing tens of billions of dollars in damages. The impacts of extreme weather events adversely affect vulnerable populations, such as Indigenous peoples, persons with disabilities, seniors, and low-income residents more acutely. Such events result in poorer air and water quality, heat-related deaths, and exacerbation of chronic diseases such as diabetes and respiratory and cardiovascular conditions.

The Economic Costs of Climate Change in Canada

In the last fifty years, the costs of weather-related disasters like floods, extreme storms, and wildfires have risen from tens of millions to billions annually in Canada. Between 2010 and 2019, insured losses for catastrophic weather events totaled over $18 billion, and the number of devastating events was over three times higher than in the 1980s. The average cost per disaster has jumped 1250% since the 1970s, and in the last ten years, the cost of weather-related disasters and losses yearly is equivalent to 5-6% of Canada’s annual GDP growth.

Healthcare systems will also become increasingly strained, limiting the ability to deliver quality care. The Canadian Climate Institute estimates heat-related productivity losses could exceed $5.4 billion and ground-level ozone costs of deaths could amount to $101 billion by mid-century due to accelerating global greenhouse gas emissions. The extent of the strain on Canada’s healthcare will depend highly on how successfully (or not) Canada and the world reduces such emissions.

The Impact of Climate Change on Indigenous Peoples

“I fear that all this change in climate, permafrost changes, it’s taking away who we are, and we’re not going to pass it on.”

–Nunatsiavut citizen, from the report The Impacts of Permafrost Thaw on Northern Indigenous Communities

Flooding and wildfires caused by climate change can drastically impact Indigenous lifeways and traditional land use. The 2024 Indigenous Resilience Report notes that climate change severely challenges Indigenous languages, knowledge transfer, ceremony, identity, health, well-being, and food sovereignty. For many Indigenous groups, hunting and harvesting is not only undertaken to support the local economy but is the basis for their cultural and social identity. In 2017, 65% of Inuit, 33% of First Nations living off reserve, and 35% of Métis hunted, fished, or trapped.

Climate change influences fish availability, the numbers of caribou and moose, shortens hunting periods, and impacts conditions for safe travel and access to traditional harvesting areas. Unpredictable weather and environmental conditions caused by climate change have made accessing traditional foods challenging and costly. Unusual short winter road seasons, for example, have forced remote Indigenous groups to find alternative ways of importing foods, resulting in higher food costs. Changing traditional food habits and increased dependency on retail food have resulted in high rates of chronic disease, including obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases among Indigenous populations in Canada.

The North, home to most of Canada’s Inuit population, is warming three times faster than the global average. Changes include unprecedented rates of summer sea ice loss, reduced sea ice in the winter, dangerous thin or “young” ice, ocean acidification, melting permafrost, and coastal erosion. Such impacts of climate change are compounded by the difficulties already experienced by the Inuit as a result of colonial policies and historic federal underinvestment.

Permafrost thaw not only threatens traditional harvesting and country foods but also significantly impacts northern infrastructure. At northern airports, runways are warping and cracking. The foundations of personal homes and businesses are failing. Permanent roads are cracking or collapsing, and it is estimated that half of winter roads will be unusable by 2050.

Indigenous Climate Action and Adaptation

In 2016, the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) Elders’ Council released an Elders’ Statement on Environment and Climate Change, acknowledging the climate crisis. The accelerating situation has resulted in the passage of eleven subsequent climate-related AFN resolutions. In 2023, the AFN formally launched its National Climate Strategy. The strategy prioritizes First Nations’ rights and knowledge systems. It demands urgent and transformative partnership from federal, provincial and territorial governments to work directly and entirely with First Nations to implement self-determined climate priorities.

Canada has announced more than $2 billion in climate action funding for Indigenous Peoples, which includes funding to improve food security in the north, transition remote and rural communities to clean energy, and protect biodiversity through the creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs). However, in the face of government inaction, many Indigenous communities are pursuing their own initiatives and unique adaptations to their changing environments, such as calling for rapid de-carbonization to meet the Paris Agreement targets.

Sovereign Seeds, a national Indigenous by-and-for seed and agricultural food sovereignty organization, has been working to advance Indigenous-led seed efforts by revitalizing seed-keeping knowledge and supporting the adaptation of cultural crops to respond to climate change, for example.

The T’eqt”aqtn’mux (Kanaka Bar Indian Band), located 18 kilometres south of Lytton, British Columbia, the site of a devastating wildfire in 2021, completed a community watershed Land Use Plan in 2015 and a Climate Change Assessment and Transition Plan in 2018, acknowledging the need for climate adaptation planning. The Nation has since invested in three weather stations, seven water gauging stations and an air quality monitor. Such tools generate daily site-specific community data and complement Indigenous knowledge to assist with forecasting, early warning systems, emergency preparedness, and response planning.

As part of the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq’s Climate Action Program, Mi’kma’ki youth launched a Pollinator Action Project in April 2019. Based on field research focused on declining pollinator populations due to climate change, the project’s findings are being used to lobby the provincial government to implement key pilot initiatives to reduce pests linked to warmer weather to preserve declining bumblebee populations. The project is an example of climate change adaptation and intergenerational knowledge transfer.

Conclusion

Supporting the adaptive capacity of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities in Canada can only be successful if integrated with other strategies such as disaster preparation, land-use planning, environmental conservation, and a national plan for sustainable development. Crucial is the concerted effort by Canada to reduce its greenhouse emissions by 40-45% below 2005 levels by 2030. Recent modelling suggests Canada is on track to achieve 85-90% of this goal. Swift implementation of planned policies is critical.

Sufficient and sustainable funding for Indigenous communities to implement self-determined climate priorities and initiatives that integrate culture, knowledge, spirituality, language, and community support remains fundamentally critical to climate change adaptation and mitigation. Approaches must be wholistic and transcend existing systemic and colonial processes.

Share the article