Introduction

The rights of Indigenous Peoples are deeply connected to treaty relations, reflecting both historic and modern commitments between the Crown and Indigenous Peoples. Treaty relations have evolved as a feature of self-governance and sovereignty since the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which established the Treaty system known today. Today, modern treaties – or Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements – are contemporary treaty agreements between Indigenous governments/Nations and the Crown.

Typically, modern treaty agreements protect Indigenous rights and autonomy, outline mutual obligation, support community wellbeing, and detail the exchange of resources (e.g., education, economic assistance, healthcare, and agriculture). Treaty agreements carry diverse meanings, values, interpretations, and immense symbolic significance for each unique First Nations, Métis, and Inuit group, sub-group, or community. This blog explores the history of treaties and modern applications in the Canadian context.

History of Treaty-Making

As a component of Aboriginal Law, the spirit and intent of treaty-making has evolved through four key phases. Each era marks significant changes in Indigenous-Crown relations:

- Historic Treaties (Pre-Confederation Era Treaties: 1701-1923)

- Peace and Friendship Treaties (Pre-Confederation Era Treaties: 1725-1779)

- Numbered Treaties (Confederation Era Treaties: 1871-1923)

- Modern Treaties or Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements (Post-Confederation Era Treaties: 1975-Present).

Treaties were meant to establish peaceful relations and outline land use, rights, and responsibilities. While early agreements like the Peace and Friendship Treaties (1725–1779) focused on alliance-building, later treaties – especially the Numbered Treaties (1871–1923) – were used to facilitate settlement and resource access in exchange for promises like education, health care, and reserve lands. Many treaties remain foundational to the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and Canada today, though their spirit and intent are often contested.

“The responsibilities of treaty people are, among other things, to recognize the interconnectedness of our relationships, which extend to all living beings locally and globally. For nêhiyawak, we enter every treaty relationship with fundamental nêhiyaw laws that inform all of our treaty principles: miyo-wîcêhtowin [good relations], wîtaskêwin [peaceful living together on the land], and tâpwêwin [speaking with truth].”

-Jessica Johns, 2025 (Briarpatch Magazine)

Contemporary Pathways to Self-Governance: Modern Treaties

In the 20th century, Indigenous self-governance and treaty negotiations were deeply influenced by colonial policies. Key legislative frameworks like the Indian Act (1867)and section 35 of the Constitution Act (1982) simultaneously upheld and impeded the advancement of Indigenous self-determination and treaty negotiations, creating significant barriers to meaningful progress. Colonial policies established conditions for achieving self-governance through treaty relations, but also entrenched systemic inequalities, thereby limiting positive outcomes and measures of wellbeing.

A 2006 study explored how treaty status impacted Community Wellbeing Index (CWB) scores between 1981 and 2006, measuring socioeconomic data markers such as education, employment, income, and housing.

It compared:

- Non-Treaty First Nations

- Historic Treaty First Nations

- Modern Treaty First Nations

- Non-Indigenous communities

In 1981, Historic and Modern Treaty First Nations shared similar levels of community wellbeing. Between 1981 and 2006, the CWB for Modern Treaty First Nations improved at nearly twice the rate of Historic Treaty First Nations. Notably, from 2001 to 2006, wellbeing stagnated for Historic Treaty First Nations, while Modern Treaty First Nations continued to advance, aligning with the pace of non-Indigenous populations.

Modern treaty implementation must therefore be carefully assessed, given the broader implications of development outcomes (i.e., social, economic, political, cultural, health, etc.). As noted in the study, there was an indirect correlation between modern treaty implementation and improved factors of CWB; however, the study did not illustrate how other variables may influence the outcome of greater CWB scores, such as regional affiliation, funding structures, other government support or intervention, and self-government status.

Modern Treaty Negotiation Processes: Stages & Implementation

For many Indigenous Peoples, treaties are a lifelong process that embodies nation-to-nation relations. Negotiating modern treaties is crucial for advancing Indigenous self-governance and Aboriginal title in Canada, establishing both a legal and constitutional framework that upholds Indigenous Peoples’ rights. Approaches to treaty negotiations vary from a range of rights, jurisdiction, sovereignties, and title obligations. Treaties and the provisions for negotiation are influenced by the government structures, customs, traditions, and relations unique to each province, territory, Indigenous government, and distinct Nation.

“While modern treaties have been critiqued as tools of assimilation and colonization, they can also be viewed as tools of self-determination in concert with a range of other agreements, actions, and resources available to Indigenous governments.”

-Stephanie Irlbacher-Fox and John B. Zoe, 2025 (Modern Treaty Implementation Project)

Treaty commissions (where present) outline the negotiation and implementation process, ensuring that treaties clearly define rights and responsibilities related to land, resources, governance, legal and regulatory frameworks, amendments, dispute resolution, and fiscal arrangements.

The British Columbia Treaty Commission’s Modern Treaty Negotiation Framework, for example, outlines a six-stage process for negotiating modern treaties, beginning with a First Nation submitting a Statement of Intent. This is followed by a readiness assessment, the negotiation of a Framework Agreement, an Agreement in Principle, a final treaty negotiation, and then ratification and implementation over time.

Simultaneously, Canada outlines the responsibilities of federal departments in implementing modern treaties. Departments must understand their obligations, assess policy impacts on treaty rights, and report annually to CIRNAC. CIRNAC leads coordination through tools like the Treaty Obligation Monitoring System (TOMS) and provides guidance, while the Department of Justice and central agencies ensure legal compliance. Oversight is maintained by a Deputy Minister-level committee, supported by the Modern Treaty Implementation Office within CIRNAC. Every five years, Canada’s modern treaty directive is evaluated, with recommendations for improvement as needed.

Recent Amendments to Modern Treaty Processes and Evaluation

Recent efforts to improve treaty implementation and accountability include:

- Evaluation of the Management and Implementation of Agreements and Treaties

- Evaluation of the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation

- Collaborative Modern Treaty Implementation Policy

Case Study Examples

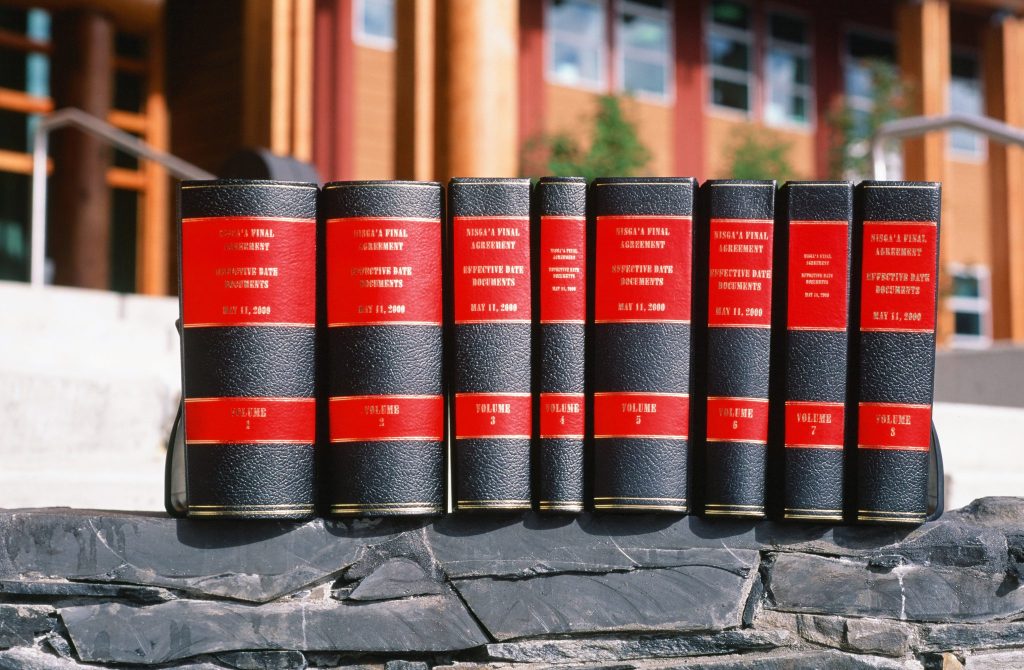

Modern treaties differ significantly from earlier agreements, both in structure and the inclusion of new stakeholders, such as First Nations, Inuit, and, more recently, Métis Nations. Since 1975, 26 Modern Treaties have been concluded, covering nearly 40% of the landmass now known as Canada. These agreements have secured Indigenous governments with ownership of over 600,000 km2 of land, $3.2 billion in transfers, co-management regimes, resource revenue sharing, and law-making powers.

Notable examples include:

The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement

The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (1993), signed by the Inuit of the Eastern Arctic, the Government of Canada, and the Government of the Northwest Territories. This landmark agreement was a crucial step in recognizing the rights of the Inuit and established the new territory of Nunavut, and addressed land claims, resource rights, and governance in the region.

The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement

The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (1975), signed by the Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee, the Inuit of Nunavik, the Government of Canada, the Government of Quebec, and Hydro-Québec, was the first comprehensive land claim agreement in Canada and set the stage for future modern treaties. The historic agreement was a significant milestone in recognizing the rights of the Cree and Inuit peoples in northern Quebec, addressing land claims, compensation, and the impact of development in the region.

Conclusion

Modern treaties are evolving tools for Indigenous self-determination and legal recognition in Canada. While shaped by colonial legacies, they offer opportunities for autonomy, cultural resurgence, and community wellbeing. Advancing treaty processes grounded in mutual respect, accountability, and Indigenous realities is key to fostering meaningful reconciliation and equitable nation-to-nation relationships.

Share the article