Introduction

“Building local capacity among northern First Nations is the only way to sustainably address staffing crises and improve access to health and education services.”

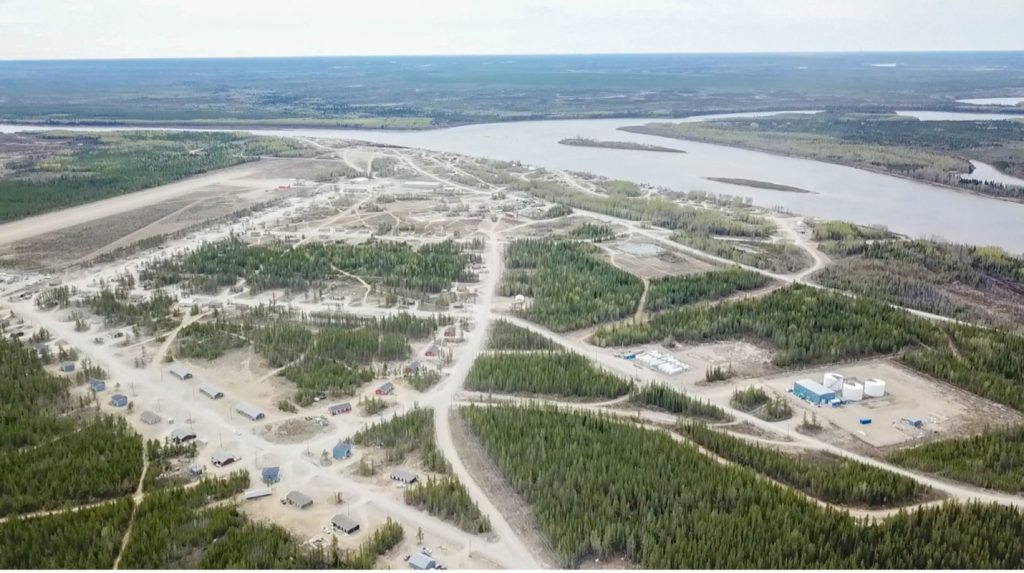

Due to the colonial nature of the reserve system and the history of forced relocations in much of Canada, First Nations are disproportionately located in remote and isolated areas away from major city centres. This poses numerous social and economic challenges for Nations, not the least of which is attracting and retaining qualified professionals such as healthcare providers, educators, and trades people. This is a major hurdle for policy makers and administrators alike, seriously undermining the successful development of local programs and services, impeding self-determination for Nations, and negatively affecting access for individuals.

Impacts of Staffing Shortages

Unfilled positions and high turnover can result in poor continuity of care for patients at nursing stations, a lack of trust and rapport between teachers and students, loss of institutional knowledge and capacity among local organizations, and high levels of depreciation of inadequately maintained infrastructure and equipment, among many things. Nations have had to close nursing stations, the only point of care in most communities, due to staffing shortages.

The difficulty of retaining regular staff has left many nursing stations heavily or even exclusively reliant on itinerant ‘agency’ nurses, temporary employees who travel and practice in different locations for short intervals. Though care from the providers is a crucial stopgap to ensuring access to care for many First Nations, this approach is far from ideal. Agency nurses are very expensive, earning much higher wages than regular permanent employees. Crucially, however, it is hard to achieve continuity of care, establish trust with patients, or build institutional cohesion and efficiency with frequent staff turnover.

A community in Northwestern Ontario, for example, recounted that 42 different nurses had come into and out of the community in a single year. Though teacher contracts are typically at least a year, First Nations schools also suffer when they invest in incentives to appeal to candidates, such as bonuses or professional development for new teachers who come to gain experience in their Nations, but then leave when a less remote job becomes available.

Barriers to Recruitment and Retention

Several factors can deter potential candidates from taking positions in Northern and remote First Nations, including concerns about isolation, lack of opportunities for family, limited housing, limited amenities including telecom connectivity, and fear of difficulty integrating into the community. A positive feedback loop can also develop whereby understaffing and attrition can create difficult work environments and burnout, further exacerbating the attrition.

The demands placed on nurses can be particularly high given the increased scope of practice sometimes required in remote Nations without a full-time physician. Likewise, systemic underfunding, higher-than-average rates of diverse needs and issues related to socio-economic adversity and the intergenerational trauma resulting from residential schools can make First Nations classrooms and healthcare settings a challenging work environment for teachers and nurses. Lack of continuity in the administration of schools and health facilities can compound these issues.

Nation-Led Strategies and Solutions

Nations have developed a range of strategies to promote working in their communities through ad campaigns, incentives, orientation programs, and improvements to amenities. Although somewhat successful, for most recruits working in the North is considered a temporary rather than permanent arrangement. There is widespread acknowledgement that the only sustainable solution to these challenges in the long term is for northern First Nations to build local capacity and overcome their reliance on a southern, largely non-Indigenous workforce. Local hires are more likely to stay in their positions and be invested in the communities, but they would also have stronger cultural competence and relate better to those they serve. Having First Nation providers could engender greater trust among those who have experienced racism in the healthcare system, and having more First Nations teachers as role models in schools would be invaluable.

Northern and First Nation labour self-sufficiency is an ambitious and long-term goal. However, there are numerous innovative programs and initiatives already underway. Some First Nations have established their own post-secondary institutions such as the First Nations University of Canada in Saskatchewan, the Kiuna Institution in Odenak Quebec, Yellowquill University College in Manitoba and the Maskwacis Cultural College in Alberta. These institutions provide flexible schedules and incorporate both ‘Western’ and Indigenous approaches to learning to support First Nations students to succeed.

The Indigenous Services Canada’s Post Secondary Partnerships Program also provides funding to support partnerships between First Nations and other post-secondary Institutions. Many Universities and colleges offer Indigenous-specific programs, especially in teaching and nursing. Lakehead University offers an Indigenous Nurses Entry Program, a bridging program for Indigenous students who want to enter nursing but do not meet the standard entry requirements. Likewise, the University College of the North in Manitoba offers flexible and distance-based nursing programs with a focus on community-based healthcare and northern health needs.

One approach First Nations in Manitoba have taken to developing teachers locally is to hire community members as Education Assistants and then support them to upgrade their education to a Bachelor of Education through the University of Brandon’s Program for the Education of Native Teachers. Cohort-based programs, such as the University of Alberta’s Aboriginal Teacher Education Program, have also provided a successful model for First Nations students, especially when training is provided on-site in First Nations communities.

Conclusion: Self-Determination Through Local Initiatives

Despite difficulties, the efforts of First Nations to build a workforce from the ground up are essential not only to meeting community needs but also achieving the self-determination Nations have long fought for. Vision and determination are present in communities, but continued support is needed from Canada, the provinces, and post-secondary institutions. True Reconciliation requires more than temporary staffing solutions; it demands long-term investments in Indigenous-led education, training, and infrastructure that prioritize community voices and leadership. By supporting northern First Nations in developing and retaining their own nurses, teachers, and skilled professionals, governments can help break cycles of dependency, foster trust in local systems, and ensure sustainable, culturally grounded care and education for generations to come.

Share the article