Introduction

The relationship between First Nations and police is complex. It is informed by historical colonial exploitation and continues to be defined by the paradox of First Nations being overpoliced out of prejudice, and under policed when assistance is needed most. This blog explores First Nations-police relations, using Nishnawbe-Aski Police Service (NAPS) as a case study of a self-determined First Nations approach to policing. It concludes by outlining lessons learned from historic and contemporary examples.

Background: Colonization and Policing

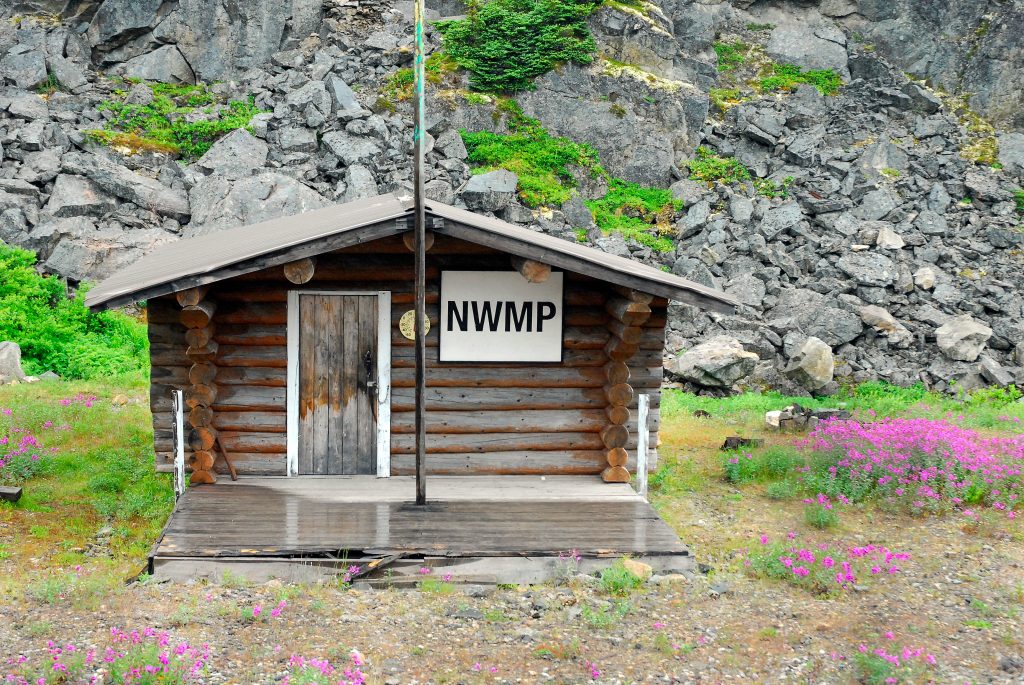

The tenuous relationship between police forces and First Nations is longstanding, traceable to the early history of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and its forerunner, the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP). The NWMP was created following the entry of Manitoba and the North-Western Territories into Canada, with the express purpose of policing settler-Indigenous relations, securing lands for settlers, and suppressing Indigenous resistance. Key this enforcement was the Pass System, which required approval from an Indian Agent to leave a reservation. If an Indian Agent felt force was necessary, the NWMP could be called upon. In limited instances where goodwill existed between the NWMP, First Nations, and Métis, the failure of the federal government to respond to local police concerns regarding unrest, and their subsequent violent response to the 1885 North-West Rebellion, only soured the relationship further.

The Band Constables Program, which provided Nations with funding for bylaw enforcement, came into effect in the 1960s, although this was not an official police force. First Nations self-administered police departments were subsequently created in 1978 under the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. From 1973 to 1989, RCMP officers could also be hired by Nations under the Native Special Constable Program. However, overt acts of police racism, represented in the deaths of Helen Betty Osborne in 1971 and J. J. Harper in 1988, only confirmed the inadequacy of policing for First Nations. Remote communities suffered from a minimal police presence, resulting in officers lacking local cultural knowledge. Conversely, police were not seen as members of the community, viewed as only showing up to make arrests.

The dissatisfaction in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly amongst remote communities, led to much needed reforms to First Nations policing across Canada. The release of 25 different federal and provincial reports on policing and the 1991 Aboriginal Justice Inquiry led to the establishment of the First Nations Policing Program (FNPP) in 1992. The FNPP created the opportunity for Nations to operate police services in much the same way as municipal police, an important step towards Indigenous self-determination. For established police forces, 52% of funding was to come from the federal government and 48% from provincial governments, although forces would abide by provincial policing standards. Police Advisory Boards (PAB) or Police Governing Authorities (PGA), were designated to keep police policy at arms-length from band politics and represent public concerns.

Case Study: Nishnawbe Aski Police Service

A success story for First Nations policing is the Nishnawbe Aski Police Service (NAPS) in northwest Ontario. During its 29-year history, there have been no shooting-related fatalities. NAPS officers are 60% Indigenous, which helps build trust with the First Nations they serve. Police officers often originate from the Nations they serve, which reduces cultural and linguistic barriers, and facilitates the use of non-violent resolutions. Many First Nations experience personal and intergenerational trauma, arising in part from the forced attendance of residential schools – which was often enforced by police. Given this history, many First Nations are suspicious of authorities that act on behalf of colonial governments. Having police officers serve in the Nations they originate from provides more empathetic and peaceful policing, where the customs and struggles of a community are understood. However, some leaders in First Nations justice policy suggest some scenarios do call for the use of force, which is often unavailable in remote communities. In this regard, non-violent solutions are still preferable, but it has been suggested they cannot entirely replace force as a means to policing.

While NAPS is better funded than most FNPP police services in Canada, it is worth noting it remains underfunded given the population and geographic area under its jurisdiction. A 2016 study found that, on average, existing FNPP police services served communities of 4,509 people, while those that disbanded were only responsible for 1,693 people. Similarly, existing police forces would, on average, work in 4.6 communities, whereas disbanded services would work in 1.7. Economies of scale are, therefore, a key consideration when establishing a FNPP police force. For this reason, the OPP acknowledged in 2016 that it would cost them $80M to police Nishnawbe-Aski Nation’s (NAN) territory, a job NAPS did at the time for only $27.5M a year.

Often, NAPS officers must perform duties that are atypical for municipal police, such as acting as firefighters or mental health professionals. While being overburdened with performing additional tasks, they can also be seen as a supplementary police force to the RCMP or provincial police. It is perhaps for this reason that FNPP are regarded as a supplemental, non-essential service. As a result, NAPS has operated for more than two decades as a “program” and not as an essential service. This also has the effect of making funding tenuous and short-term. The growth of self-administered policing on-reserve requires two foundations: the right to self-determination when governing First Nations services, and secondly, the need to treat First Nations policing as an essential service.

Despite the use of PABs and PGAs, issues of accountability persist. As an example, NAPS, like other FNPP services in Ontario, was created without a special investigations unit to investigate internal misconduct. It was not until 2019 that NAPS was brought under the Ontario Police Services Act and Ontario Civilian Police Commission. Although disciplinary actions occur, it is often on an ad hoc basis, and has perhaps been too permissive of internal misconduct. Further accountability mechanisms are needed if First Nations are to truly be policed in a way that is self-determined.

Despite challenges, NAPS has been able to develop a model for policing that better suits the needs of First Nations in northwestern Ontario than that of the Ontario Provincial Police or the RCMP. For example, NAPS recently signed an agreement with the Thunder Bay Police Service in Ontario. Thunder Bay has garnered media attention for police corruption and horrific institutional racism against First Nations peoples. The choice to work with NAPS is an important step towards addressing this growing crisis, as NAPS and the Thunder Bay Police Service have overlapping jurisdictions, and the victims and survivors of many anti-Indigenous crimes in Thunder Bay come from NAN member Nations.

Lessons: A Long View of Police Reform

The process of building a trusting relationship between First Nations and police in Canada will take time and many years of reconciliation. Centuries of trauma, caused by imposed colonial policies, and decades of discrimination and systemic racism, has created a general relationship of mistrust between First Nations and police forces. This reality cannot be ameliorated easily: it will require the creation of policing institutions that are accountable to the people they serve, represent community-needs for safety, and are a symbol of self-determination for First Nations. This cannot be done with only minimal support from the federal and provincial governments.

Final Thoughts

The issues affecting First Nations are complex, and it is inadequate to impose or scale up colonial models for policing. Police officers and administration who are invested in the well-being of the Nations they serve are important, but it will be crucial to fund the development of FNPP in the long term and allocate sufficient resources. This will not repair the relationship between First Nations and colonial police forces, but it can forge new relations that promote safer Nations and more accountable policing.

Share the article