Introduction

Indigenous populations living off-reserve in Canada are disproportionately unhoused or underhoused relative to the overall population. A complex array of factors, including ongoing colonialism, Indian Residential Schools, racism and discrimination, and federal underfunding of housing initiatives for Indigenous populations in urban centres compounds and exacerbates this issue. In recent years, Canada has committed to greater support for affordable housing initiatives for Indigenous peoples living off-reserve, such as spending as part of the National Housing Strategy and the recently initiated Urban, Rural, and Northern Indigenous Housing Strategy. Housing First, an approach for addressing chronic homelessness, is likewise gaining traction. The unique cultural context of Indigenous peoples’ lived experiences and right to self-determination must be respected regarding Indigenous anti-homelessness and housing affordability initiatives.

Types of Homelessness

The Canadian Observatory on Homelessness defines Indigenous Homelessness in Canada as:

“Indigenous homelessness is a human condition that describes First Nations, Métis and Inuit individuals, families or communities lacking stable, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect, means or ability to acquire such housing. Unlike the common colonialist definition of homelessness, Indigenous homelessness is not defined as lacking a structure of habitation; rather, it is more fully described and understood through a composite lens of Indigenous worldviews. These include: individuals, families and communities isolated from their relationships to land, water, place, family, kin, each other, animals, cultures, languages and identities.”

-Jesse Thistle, Resident Scholar of Indigenous Homelessness

Generally, homelessness is described as, “the situation of an individual, family or community without stable, safe, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect, means and ability of acquiring it.” There are some varieties based on the nature of the homelessness at any given point in time:

- Unsheltered (absolute) homelessness: People who are living in public or private spaces, without permission and in places not fit for human habitation, such as makeshift or temporary tents.

- Emergency sheltered homelessness: People in shelters made to temporarily house those who are homeless or at-risk of homelessness. This category includes homeless shelters, shelters for those escaping domestic violence, or emergency shelters for those displaced by natural disasters.

- Provisionally accommodated: Includes persons in transitional housing, those temporarily living with family or friends (“couch surfing” or “hidden homeless”), those without housing living in motels or hotels, those in institutional care without permanent housing, as well as recent immigrants or refugees staying in transitional facilities.

- At risk of being homeless: This includes those who are experiencing a serious immediate risk of becoming homeless due to domestic violence, unemployment, or another specific housing situation but are not yet homeless. It also includes the precariously housed – those in core housing need. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) defines core housing need as households spending more than 30% of their pre-tax income on housing (unaffordable housing) or living in housing without enough bedrooms for the size and nature of the household (unsuitable housing) or living in housing that requires significant repairs (inadequate housing).

Homelessness is also categorized by duration. Employment and Social Development Canada classifies the following subtypes of homelessness:

- Chronic Homelessness: Periods of homelessness amounting to at least six months over the past year or repeated periods of homelessness over three years with a total length of 18 months staying unsheltered, in emergency shelters, or couch surfing.

- Cyclical and Episodic Homelessness: Pattern of homelessness where a person moves in and out of homelessness based on circumstances, such as changes in employment, losses of income, domestic situation, or other factors.

- Temporary Homelessness: Limited and unrepeated occurrences of homelessness, such as those that result from nature disasters or house fires.

Homelessness and At-Risk Indigenous Populations

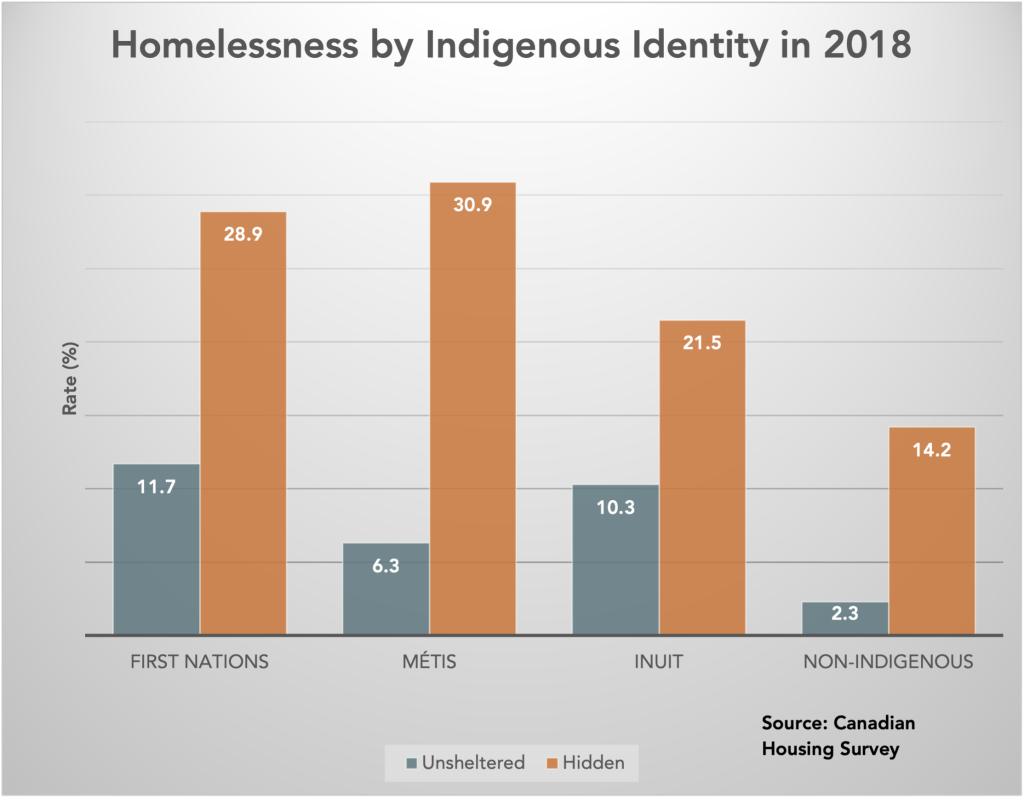

Indigenous identity populations had greater rates of homelessness than the non-Indigenous population, according to the 2018 Canadian Housing Survey (CHS). First Nations (11.7%) and Inuit (10.3%) had higher rates of unsheltered homelessness than the Métis (6.3%).

The rate of hidden homelessness was higher for Indigenous identity populations than for the non-Indigenous Canadians, with First Nations (28.9%) and Métis (30.9%) reporting higher rates of hidden homelessness than the Inuit (21.5%).

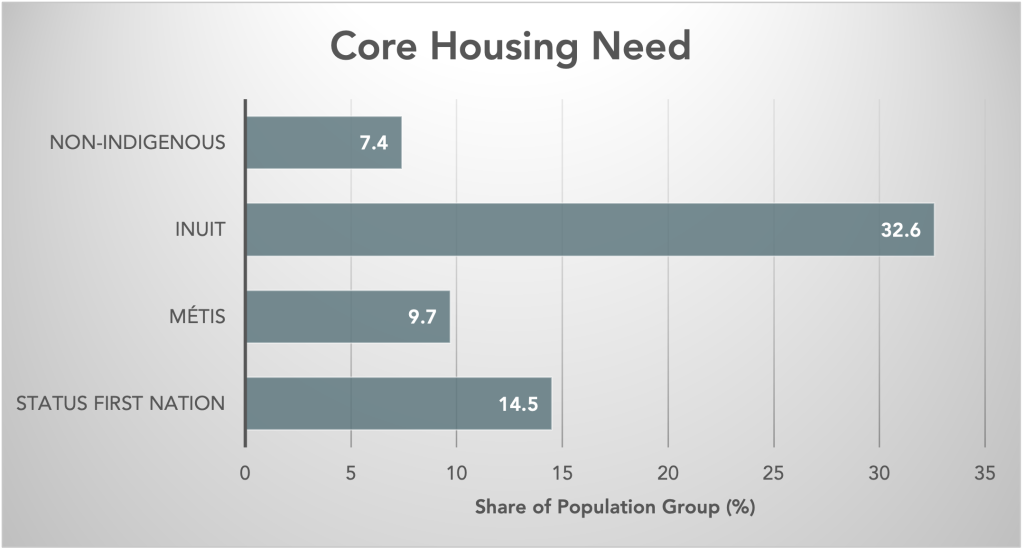

Working with Statistics Canada, the CMHC derives core housing need estimates from census data. These estimates do not include households on-reserve, households with no income, and households with shelter-cost-to-income ratios of 100%. Households in core housing need may be regarded as part of the precariously housed at risk of homelessness. Based on 2021 census data, share of the population in core housing need is greater for each Indigenous identity group than for the non-Indigenous population (7.4%). Across Canada this ranges from 32.6% for the Inuit, 14.5% for First Nations, and 9.7% for the Métis.

A 2021 report by the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO), based on 2016 data, estimated the cost to address off-reserve Indigenous housing needs to varying degrees under different programs. This report estimated yearly costs ranging from $122 million to $1.4 billion.

In the federal Budget 2023, $4 billion over seven years, starting in 2024-25, was proposed to institute an Urban, Rural and Northern Indigenous Housing Strategy for Indigenous persons living off-reserve. As part of this, the CMHC issued a request for proposals to establish a National Indigenous Housing Centre.

Housing First and the Indigenous Context

Housing First is a model for ending homelessness that focuses on moving people experiencing homelessness into housing as a first step, rather than focusing on “readiness” prerequisites to housing. This approach emerged in the 1990s and went against the then-dominant view that people experiencing serious mental illness and long-term homelessness could not be housed without addressing their mental illness, substance use, or rehabilitation needs first.

Evidence of the effectiveness of this model has grown. Housing First has been incorporated into housing programs for veterans by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. US Veterans Affairs Housing First approaches are informed by the Pathways to Housing model, which was developed by Dr. Sam Tsemberis in New York in the 1990s. There is an associated fidelity scale for following to the Pathways model. This approach prioritizes scattered-site housing with rented units in independent, private rental markets to give clients more choice and prevent stigmatization.

Finland instituted its own Housing First policy in 2008, which operates through partnerships between the Finnish national government, municipal governments, and non-governmental organizations. A systems-wide approach, Finland’s policy was achieved with the conversion of emergency shelters into housing and the construction of new social housing. The total number of homeless individuals in Finland declined from 8,000 persons in 2008 to around 3,700 people as of 2022. Unlike the Pathways model, Finland’s housing first approach involved congregate housing.

Within the Canadian context, Housing First approaches became prominent with the At Home/Chez Soi research demonstration project. $110 million was allocated in 2008 by Canada for a five-year project to generate knowledge about the effective approaches for people experiencing serious mental illness and homelessness. This lead to the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) and stakeholders in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Montreal, Toronto, and Moncton implementing a pragmatic randomized controlled trial of Housing First. At Home/Chez Soi used the Pathways Housing First Fidelity Scale to assess how well each city’s Housing First demonstration project conformed to the “standard” Pathways approach.

For the Winnipeg Housing First Research Demonstration project, adapting the model to Indigenous needs was vital. Intervention teams housed in Mount Carmel Clinic, the Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre of Winnipeg, and the Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata Centre delivered Housing First services during the project. Tailoring this program to the Indigenous context included Indigenous input into project leadership, a more community-oriented focus, strengths-based approaches, and integrating Indigenous ceremonies and protocols. Training on Indigenous history, learning from Elders, and training in trauma-informed care was included for staff. Need for further adaption of the Housing First model was identified in Winnipeg, however. Some Indigenous participants found scattered-site private accommodations isolating. Need to acknowledge the fluidity of migration between reserves and urban centres is another point that has been noted.

Final Thoughts: Going Forward

Indigenous populations living off-reserve have long faced disproportionate challenges obtaining suitable, adequate, and affordable housing and experience higher rates of homelessness than the non-Indigenous population. Canada, recognizing this gap, has initiated some investing to close service gaps. Understanding the unique needs of Indigenous populations, listening to Indigenous peoples, and, most importantly, respecting the Indigenous right to self-determination will be essential for the success of current and future off-reserve housing programs.

Share the article