Introduction

As defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) “performance measurement seeks to monitor, evaluate and communicate the extent to which various aspects of the health system meet their key objectives.” Crucially, these measurements provide input for policy makers to improve their understanding of how the health system works and provide detailed information to identify and correct problems affecting the well-functioning of the health care system.

For example, assessing the health workforce’s availability, distribution, skills, and motivation is essential for the appropriate functioning of a health system, as stated by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Performance indicators such as the density of health workers per 10,000 population, the number of graduates by occupation (e.g., medical and nursing), or the distribution of health workers by geographical area (e.g., metropolitan or remote) help answer relevant policy questions regarding the recruitment and retention of health workers and a country’s capacity to build an adequate supply of health workers and manage shortages.

There are serious concerns, however, about the effectiveness of non-Indigenous models and performance measures focused on individual health outcomes and biomedical models, to the detriment of a more holistic approach to health and well-being for evaluating Indigenous health. There is evidence that performance measurements of health for Indigenous peoples are underdeveloped at the local and regional information system levels, there is a lack of Indigenous-specific frameworks and indicators, and there is no formalized feedback to Indigenous communities. In Canada, for example, performance measurement data are not consistently available for northern regions. Additionally, indicators need to be adapted to the context of northern Indigenous communities and First Nations.

Given the importance of performance indicators to inform public health policies, Indigenous communities in Canada would benefit from Indigenous-specific performance measurements of health as they will increase the ability to respond to specific Indigenous health-related needs, including the need for structural changes to eliminate racism against Indigenous people in the health care system, enable local Indigenous communities to make informed decisions regarding health policies and incorporate contextually appropriate indicators according to Indigenous cultural values and definitions of health. Crucially, Indigenous peoples must participate in the co-design of Indigenous-specific performance measurements of health.

Performance Measurements of Health in Canada

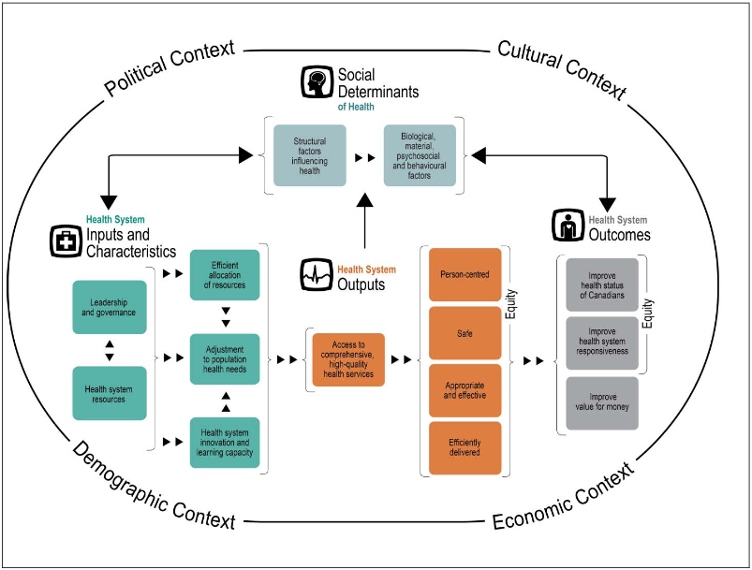

In line with international efforts, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) developed a Performance Measurement Framework (PMF) for the Canadian Health System. The PMF offers a conceptual framework and a series of indicators for analyzing and measuring the performance of the healthcare system in Canada. It builds and expands on the Health Indicators Framework previously developed by CIHI and Statistics Canada in 1999.

According to the CIHI, the PMF “proposes a unifying health system performance measurement framework that is designed to support the performance improvement priorities of Canadian jurisdictions by reflecting the expected causal relationships among dimensions of health system performance.” The PMF has four main components that correspond to the proposed expected causal relationship among components within the system:

- Health system outcomes: the ultimate goals of the health system.

- Social determinants of health: factors that shape individuals’ and families’ socio-economic position and interactions affecting health, such as income and social status, education and literacy, and gender and ethnicity.

- Health system outputs: characteristics of the health services (or outputs) produced by the health system.

- Inputs and characteristics of the health system: factors allowing and explaining the health system’s performance.

The PMF specifies different dimensions for measuring performance for each component. For example, to assess the system’s performance regarding the health system’s output component, measuring dimensions include access to high-quality services and the attributes of those services being person-centred, safe, appropriate, and efficiently delivered.

Importantly, according to CIHI, the proposed framework has a “high degree of correspondence” to the goals established by different Canadian jurisdictions in their strategic and service delivery plans. This correspondence allows the use of the proposed framework and indicators to assess the health system performance in various provinces and territories. The framework allows one to trace back and forth the effects of a component’s performance by following the proposed expected causal relationship among components within the system.

A novelty in the PMF for the Canadian health system is the consideration of the social determinants of health, which acknowledges the importance of the social context for health. The framework recognizes that political, cultural, demographic, and economic factors matter for understanding health inequalities. The framework considers two different levels of interaction to incorporate these social determinants: structural and intermediate. First, structural factors determine an individual’s socioeconomic position within society. Second, different societal positions determine exposure to more healthy or unhealthy living conditions (i.e. behavioural and biological factors) that contribute to determining an individual’s health conditions. These specific interactions contingent on an individual’s socioeconomic position are referred to as intermediate factors.

Indigenous Health Performance Measurements

Despite the efforts to improve the PMF, the persistence of health inequalities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada indicates difficulties with the capacity of (re)action of the Canadian health system to address the Indigenous Peoples’ health-related concerns.

There is evidence, for example, that Canada’s health system performance measurement infrastructure is underdeveloped for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. Regarding data, some limitations include poor quality, distrust between Indigenous communities and external data collection processes, indicators informing fiduciary accountability instead of public health policy planning, limited data access and governance, use of inappropriate performance indicators, and lack of inclusion.

Poor Quality of Data

Most data are available at the national or provincial/territorial level but not at the community or First Nation level. Therefore, it is difficult to design evidence-based policies to improve the health system performance for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. Moreover, available indicators fail to incorporate Indigenous conceptualizations of health; the identification of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people in health care data is not consistent; and there is little involvement of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people in the design of indicators, data collection, and analysis.

Distrust

There is a lack of trust in PMF indicators as they are an external process for Indigenous communities. Previous negative experiences between Indigenous Peoples and government organizations or researchers working on communities to collect data instead of working with communities lingers. Further, the increasing gap in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada raises concerns about the effectiveness of PMF indicators in improving the health system for Indigenous Peoples.

Fiduciary Accountability Versus Public Health Policy Planning

Many health indicators primarily satisfy fiduciary accountability requirements and are limited in their use in designing public health policies to improve the health care system for Indigenous communities.

Limited Data Access and Governance

The fact that First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people have limited or no access to Indigenous-specific health indicators limits their empowerment to improve health system performance and raises concerns about the use of PMF data and the application of the right of Indigenous people to own, control, access, and possess (OCAP©) their Indigenous-specific health information.

Inappropriate Performance Indicators

Given disparities in health’s social determinants, PMF indicators must be contextually appropriate. An Indigenous-specific health measurement system must include broad definitions of health with a holistic, community-level focus beyond individual health measures. For example, a recent study highlights the need for more contextually appropriate PMF indicators in the case of maternity health in circumpolar territories.

Despite cultural differences, Indigenous Peoples in circumpolar territories face similar challenges concerning health services delivery, including low population densities and extreme weather conditions. These characteristics defy the health system’s well-functioning and raise concerns regarding some PMF indicators. The practice of evacuating low-risk women in circumpolar regions for labour and birth, based on defined Canadian maternity care indicators and the practice of medical evacuation for access to secondary and tertiary level care, affects local birth programs and has noted adverse effects for patients, kinship circles, and communities. “Where possible, it is considered best practice to provide care for labour and birth closer to home.” However, PMF indicators do not measure this problem because of the minority of women living in Canadian circumpolar areas. The study concludes that it is relevant for health systems that attend to Indigenous populations living in circumpolar territories to have PMF indicators that account for Indigenous knowledge and practices.

Lack of Inclusion

The PMF limitations identified inevitably exclude Indigenous peoples from the health system.

“These systems will be most useful if there is Indigenous community involvement at all stages of development, implementation, and ongoing use.”

-Marcia J. Anderson & Janet K. Smylie (2009)

Addressing issues regarding PMF indicators is urgent in narrowing health inequalities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples in Canada as they provide crucial information for policy makers to swiftly identify and rectify the issues adversely affecting Indigenous Peoples’ health. It is encouraging to know that CIHI is currently working with Indigenous leaders to support Indigenous health priorities, including PMF improvements and the fact that there are some participatory approaches to co-designing Indigenous health indicators in place. This work must be expanded and Indigenous Peoples and communities be more meaningfully engaged and included in the process.

Final Thoughts

Addressing the gaps in Canada’s health performance measurement frameworks is critical to advancing equity for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. Without Indigenous-specific indicators that reflect community values, cultural contexts, and lived realities, health system data will continue to fall short in driving meaningful change. By ensuring Indigenous leadership, co-design, and control in the development of these measures, Canada can move toward a more responsive, inclusive, and accountable health system that supports the well-being of all peoples.

Share the article