Introduction

Supporting mental health and well-being within the various levels of trauma that Indigenous Peoples experience in a colonial-based society is an ongoing challenge identified by Indigenous leaders and organizations. Combined with lingering residential school trauma, multigenerational substance use, widening health outcomes, socioeconomic gaps, and unprecedented levels of suicidal activity across First Nations in Canada in recent years, a robust Indigenous-led response is required to ensure overall wellbeing for future generations.

Western Approaches to Mental Health

The Western approach to mental health and wellness has historically been biomedical in nature, modelling mental health as the biological vitality of individuals’ nervous systems. Typical Western interventions for mental health include symptom reduction, medication, and behavioural strategies for improving mental wellness. Such interventions deserve recognition for their utility in modern medicine but must be seen as fundamentally determined by Western values and Eurocentric approaches to health and wellness. To indigenize the concept of mental health, the approach to mental wellbeing must return to Indigenous values and perspectives. Secondarily, there must be translation between Western and Indigenous perspectives of the concept.

Indigenous Approaches to Mental Wellbeing

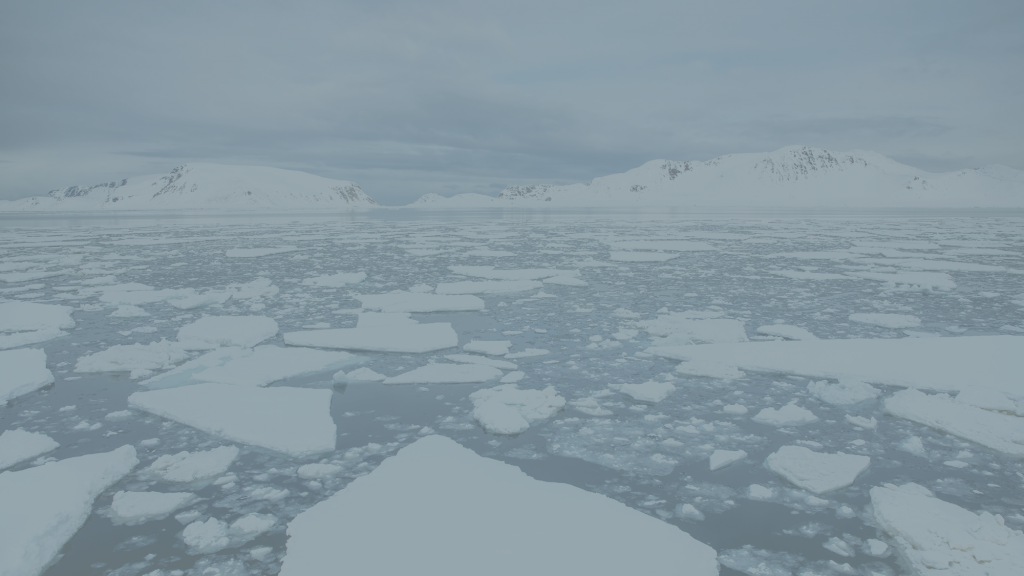

For numerous First Nations and Indigenous communities in Canada, cultural identity and involvement is paramount to mental wellness. Familial connectedness, spirituality, cultural safety, and relationship to the land have all predicted, and in some models infer the causality, of positive mental health outcomes in First Nations citizens. Practices that remove children from their kinship circles and a lack of resources to pass on knowledge of Indigenous languages and activities both predict morbidity of mental illness. Accelerating climate change, which subjects people to unforeseen loss, damages and changes food systems and ancestral environments, and impacts the relationship to the land and to each other, further providing the possibility for negative mental health outcomes.

An Ongoing Mental Health Crisis for Indigenous Peoples in Canada

Negative mental health outcomes have, in some communities, reached critical levels. In 2019, the Eskasoni Mi’kmaw Nation in Halifax experienced five deaths by suicide in a span of five weeks. In early 2024, Nishnawbe Aski Nation held an emergency meeting to address an alarming level of suicide deaths and suicide attempts amongst youth within its northern Ontario First Nations membership.

A 2023 report found that more First Nations citizens, particularly women, are dying from toxic drugs compared to non-First Nations people. Further, depression and anxiety morbidity amongst First Nations people is multigenerational and disproportionately high. A sample of residential school survivors in Canada indicated high rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviours; out of 127 participants, only two had not been diagnosed with a mental health disorder.

In response to such crises, interviews and focus groups with Elders conducted in 2019 suggest a relationship-driven framework of familial, community, spiritual, and land-based connection for decolonized mental health.

“When your soul is sick, what you need is not a pill, it’s to go back into that place of connection to family, to homeland, to knowing who you are…”

– Dr. Grace Kyoon-Achan, University of Manitoba

To decolonize mental health, focusing on eliminating symptoms or behavioural-based interventions is merely one piece of a larger, holistic puzzle. Individuals require a framework for self-determination that creates space to connect with others, the land, and their cultures to gain a unique sense of purpose and meaning.

Case Study – Mental Wellness Programs (MWP) for First Nations in Ontario

Dr. Melody Ninomiya and her team were enlisted by five First Nations in Ontario to collaborate on research-to-action programs for their citizens. Projects had four phases: 1) Learn, 2) Identify, 3) Implement, and 4) Share.

In the learning phase, the researchers collaborated with community leaders and service providers to identify the strengths and weaknesses of their Nation’s health and wellness. Citizen-determined questionnaires, surveys, the sharing of lived experiences, and focus groups were used to collect local data. After the Nation was surveyed, the identify phase featured a Community Advisory Circle which received feedback from citizens and discussed land-based interventions to improve mental health and wellness. Identified interventions were introduced in the implementation phase. The research team collected data, based on the methodologies recommended by the Advisory Circle, which evaluated the efficacy of the program. Once the intervention was complete, the final step involved the Nation deciding whether the program had been useful and if they wanted to share the knowledge they had gained, and if they did, who they would share it with.

This program built enhanced community supports and resiliency factors. It was also self-determined and an exemplary example of knowledge-sharing for First Nations addressing high priority issues related to mental wellness. Self-determined, Nation-specific approaches are not only possible, but have the potential to demonstrate promising results.

Finding Translation between Western and Indigenous Definitions of Mental Wellness

The efficacy of Indigenous-led approaches to mental health is an opportunity to explore where translation between Western and Indigenous definitions of mental wellness can be found. A focus on community connection and integration of the body and self are also emphasized in Western approaches to mental wellness, as is evident in the ego and self-psychologies of Carl Jung and Alfred Adler. Such approaches have been integrated into recreational activities and individual practices (i.e., hot yoga, team sports, and recovery groups like Alcoholics Anonymous). Likewise, when a person’s relationship to their environment changes, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic or when a family member becomes ill, they may also feel a disconnect between their peers, the land, and their personhood.

Sweats and the hallucinatory symptoms of traditional ceremonies are also not exclusive to Indigenous methodologies, with recent studies demonstrating the possible efficacy of psychoactive substances in treating suicide ideation and depression. An Indigenous medicine wheel or sacred hoop, viewed by some First Nations as a symbol of the interconnectivity of all aspects of one’s being (emotional, spiritual, physical, and mental) was echoed in Carl Jung’s first mandala, which he describes as an expression of the total psychological self and divided into four quadrants. Commonality between Western and Indigenous approaches to mental wellness indicates a fusion of techniques may be drawn upon to create a unique toolkit to address individual or community-specific issues. Ultimately, a self-determined approach based on self-identified needs is key.

Conclusion

Indigenous-led or self-determined mental wellness programs which have found success could be translated to other communities or even educational institutions to further decolonize mental health and wellbeing. Providing mental health professionals with the means to build programs around student wellness, collaborating with Elders and community members to design programs to improve mental health across their respective community, could also have positive effects on not only mental wellness but also on educational outcomes like GPA, graduation rates, and First Nations post-secondary admissions. Integrating community identity, as well as self-exploration, has the potential for positive implications that go beyond the prevalent “diagnose and dose” process which currently blankets most mental health approaches and interventions.

Share the article