Introduction

A genuine interest in improving the well-being of Indigenous people in Canada and abroad calls for a commitment to critically analyzing and revising the current governance structures of Indigenous peoples and the effectiveness of the policies that emerge from this status quo.

In Canada, for example, the critical living conditions of many Indigenous people and the growing disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in terms of poverty, wealth, education, and health outcomes, among others, suggest we must be open to new ideas and question ongoing assumptions. The process of questioning assumptions is crucial in our efforts to rethink current governance structures with the ultimate goal of improving the well-being of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples in Canada.

The work of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc member C.T. Manny Jules, Chief Commissioner of the First Nations Tax Commission in Canada, in debunking the myth that Indigenous groups were “socialist,” is a noticeable example of discussions that must occur. According to Jules, debunking such a myth paves the way for vibrant Indigenous economies to be renewed: “the myth that we were socialists, that all of everything that we ever owned was held in common, that we did not have an economy, that we did not contribute, we did not have trade, all of those notions are part of the mythology that we have to destruct.”

Renewing Indigenous Economies

Meaningful research-based discussions aiming at promoting policies that increase economic development and wealth for Native Americans are taking place at the Tulo Centre of Indigenous Economics in British Columbia and the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. This blog features several such discussions in light of the recent publication of Renewing Indigenous Economies(2022), by Terry L. Anderson and Kathy Ratté, which details research findings from the Renewing Indigenous Economies project at the Hoover Institute. Crucially, this research project incorporates experiences, knowledge, and teachings of Indigenous tribal leaders and citizens of Indigenous nations across North America.

Renewing Indigenous Economies emphasizes that crucial elements of today’s more developed economies, including private property rights and markets, were already present in Indigenous societies before encounters with Europeans: “…America’s Indigenous people created wealth through specialization and trade, recognized the value of the property, and developed institutions that helped them create levels of comfort and security found in few other parts of the world, and even some examples of enviable splendor.” However, given today’s precarious socioeconomic conditions of many Indigenous communities, the book asks, among other questions, “What caused the demise of traditional [Indigenous] economies?” Further questions include, “what are the barriers to economic growth?” and after key barriers have been identified, “can they then be dismantled and overcome?”

In answering these questions, the concept of institutions is essential to Renewing Indigenous Economies’ argument. In a nutshell, after the Indian Wars of the nineteenth century, the new institutional setting, i.e., the federal Indian law, replaced tribal laws and other traditional formal and informal institutions, thus changing “the rules of the game” for Indigenous people in today’s North America.

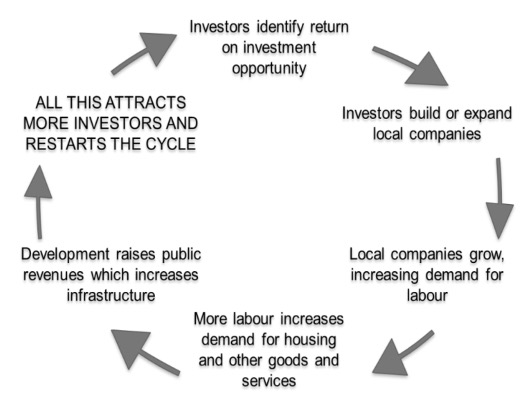

The new colonial institutional setting established a paternalistic approach where the federal government is responsible for protecting tribes and tribal property, therefore constraining tribal sovereignty and excluding Indigenous communities from ownership and the virtuous circle of economic investment, employment, income, consumption, and more investment – a cycle based on ownership and legal certainty (See Figure 1). Under this new institutional order, Indigenous communities heavily depend on federal funding, i.e., transfers, rather than their own resources and capacities to generate prosperity for their citizens as they did before.

The importance of institutions for economic performance, and the development and prosperity of nations, is highlighted in the economic profession. Douglas North, Nobel Prize in Economics (1993), highlighted the importance of institutions as they provide the rules and incentives shaping economic agents’ behavior. More recently, Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson (Nobel Prize in Economics, 2024) and Acemoglu and Robinson (2012) highlight the importance of institutions for economic prosperity and development. In short, whereas inclusive institutions lead to prosperity by providing equal opportunities and incentives for investment and innovation for individuals in society under secure property rights, extractive institutions prevent economic growth by discriminating in favor of the elites.

The Importance of Institutions: Examples of Success & Failure

Renewing Indigenous Economies provides examples highlighting the importance of institutions for either the economic success or failure of Indigenous communities. In the case of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe in Colorado, as an example of economic success, the nation obtained its sovereignty and economic independence in 1982 after a lengthy judicial journey originally initiated in 1896. Without the federal government deciding their economic future, and with ownership and control of resources, including water, land, and minerals in their territory, the nation initiated their own gas company in 1992. It evolved into a gas exploration conglomerate that allowed for a diversified economy with business in different sectors ranging from biofuel production to a casino and hotel. This new diversified economy allowed the reserve to overcome severe poverty, unemployment, and issues associated with a lack of education and health services.

Several examples included:

- The Southern Ute were able to take control of and manage the reservation’s infrastructure.

- Runs its own medical clinic.

- Built a state-of-the-art recreation center.

- Introduced a Ute Language program in its schools.

- Developed alcohol and substance use treatment centers.

- Opened an Elder center.

- Developed job training programs.

- Introduced scholarships (drawn from oil and gas profits) for every Southern Ute member who wishes to attend post-secondary education.

- Provides dividends to every Southern Ute citizen aged 26-59.

- Provides retirement benefits to every Southern Ute citizen aged 60 or older.

In contrast, a story of economic failure is true for the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. Despite being sited on top of one of the largest oil and gas reserves in the United States – the Williston Basin – the Indigenous population remains severely socioeconomically disadvantaged. This can partly be attributed to the institutions in place (e.g., rules and laws) blocking economic opportunities for the Indigenous communities with incredibly restrictive transaction costs. While only four steps are needed to obtain a permit to drill a well on off-reserve land, 49 steps and four federal agencies are required for a permit on-reserve. Consequently, all benefits of the economic activity associated with the rich Williston Basin have occurred outside of the Fort Berthold Reservation.

Concluding Thoughts

Renewing Indigenous Economies concludes by arguing for inclusive legal, fiscal, and financial institutions, which are essential for making Indigenous economies sustainable and profitable. In Canada, for example, First Nations have called for a renewed fiscal relationship with Canada for decades. Canada has promised the co-development of such, but progress has been slow and halting, without the significant institutional change required to truly transform First Nations economies.

In sum, Renewing Indigenous Economies argues that Indigenous economies can be vibrant again – beyond federal transfers – if legal and economic frameworks return ownership and access to resources and revenues to Indigenous people, as was the case traditionally and historically before the onslaught of colonial paternalistic governance and economic practices.

Share the article