Introduction

In recent years, harm reduction practices and policies have gained salience across Canada. Harm reduction aims to reduce harm to physical and mental health that can result from substance use, without necessarily requiring abstinence as a precondition. Advocates highlight harm reduction’s potential to reach a larger population, its lower financial cost, and its potential to reduce crime. Others, however, view harm reduction as controversial, raising concerns that it may inadvertently enable substance use.

Among First Nations, discussions around harm reduction are equally complex and diverse. Many leaders, health professionals, and community members are actively exploring how different approaches – both harm reduction and abstinence-based – align with their cultures, practices, and community wellbeing. This article provides an overview of how harm reduction is being discussed and applied in some First Nations contexts, recognizing that there is no single approach or consensus.

What is Harm Reduction?

The purpose of harm reduction is to minimize the negative effects resulting from substance use. In 2020, the financial costs of harm resulting from substance use in Canada were an estimated $49.1 billion. Almost half of this amount came from lost productivity, while increased healthcare and criminal justice costs were also key drivers. On an individual level, harms can include injury, depression, relationship problems, financial difficulty, and legal challenges.

To minimize these harms, some practitioners emphasize the importance of meeting people “where they’re at,” acknowledging that cessation of substance use is not always an immediate or realistic goal. This perspective focuses on creating a caring and supportive environment where individuals can improve their well-being at their own pace.

Harm reduction also intersects with broader social justice considerations. Class, race, gender identity, and other social factors influence how people experience addiction and access support. Consequently, there is no singular or universal approach to harm reduction – or to healing more broadly – as all interventions must be tailored to the needs, values, and experiences of the individual and community.

The Harms of Colonialism

Decolonization is central to understanding substance use and healing within First Nations contexts. Historical and ongoing colonial policies have shaped how substance use is understood, treated, and policed. For centuries, colonial authorities played a role in the trafficking and regulation of addictive substances, including alcohol, opium, cannabis, and later morphine and heroin.

The criminalization and policing of substance use, such as in the North West Territories, often reflected colonial power structures. Racist stereotypes – such as the “firewater” myth that suggested a biological First Nations intolerance to alcohol – were used to justify discriminatory policies. For example, under the Indian Act, alcohol sales to First Nations people were banned, while settlers faced no such restriction. These double standards reflected assimilationist intentions rather than genuine concern for community health.

The resulting harms were compounded by intergenerational trauma, displacement from land, and experiences such as Residential schools. These legacies have contributed to complex relationships with substances across communities today.

Many Indigenous scholars and community leaders note that punitive or criminal responses to substance use often fail to address these broader contexts. Others, however, emphasize community protection and abstinence-based measures as essential to healing. This diversity of perspectives underscores the importance of understanding substance use within local histories, values, and priorities.

Land as Medicine

The land and people are intrinsically connected. Much like a nurturing relationship, the land can teach and provide guidance. An important lesson often learned from the land is that there is no shame in seeking help. Many communities describe this as part of a wholistic understanding of health and balance.

Land as medicine, or land-based learning, can also be an act of reclamation and reconnection for Indigenous peoples. Relationship to land, language, and culture contributes to a sense of purpose and healing. For some Nations, reconnecting with land can complement approaches to substance use and wellbeing, including – but not limited to – harm reduction. For others, land-based practices are more closely tied to abstinence and restoration. Both approaches aim to address the root causes of harm and strengthen individual and community wellness.

Ceremonies

The connection to the land, as well as to Creator, Mother Earth, ancestors, and all living beings, can be strengthened through ceremony and spiritual practices. Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and peers often share teachings and support through these gatherings, creating spaces for healing and self-reflection.

Ceremonies can play different roles within First Nations’ approaches to wellness. Ceremonial approaches are diverse, ranging from Sweats, Smudging, Pipe Ceremonies, and Powwows. These present various ways to meet people “where they’re at,” providing what is needed rather than what is available. Ceremonies such as these may complement harm reduction approaches by helping individuals find belonging and strength. Others may require abstinence or focus on spiritual purification. Both reflect community values and teachings.

Some ceremonies follow specific protocols — such as abstinence requirements or gender-based roles — that can affect who is able to participate. Many communities are reflecting on how to honour traditional teachings while also supporting inclusion and accessibility, particularly for members on healing journeys.

Examples of Implementation

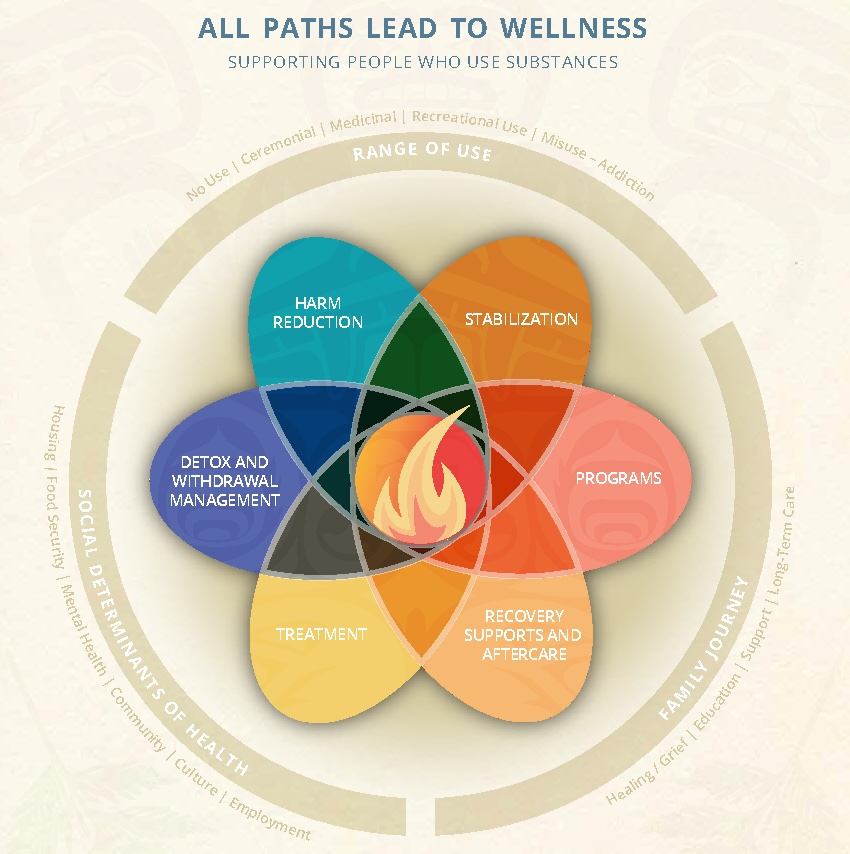

Across Canada, First Nations and Indigenous organizations are developing their own approaches to substance use and wellness, reflecting a diversity of philosophies and community priorities. These initiatives show how harm reduction, abstinence, and culturally grounded healing can coexist within broader frameworks of self-determination and health sovereignty.

In British Columbia, the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) has adopted a Policy on Indigenous Harm Reduction that emphasizes “walking with people where they’re at” and weaving cultural teachings, ceremony, and connection to land into wellness supports. FNHA’s programs – such as community-driven naloxone distribution, anti-stigma campaigns, and culturally informed outreach – illustrate how Indigenous values can be integrated into public health efforts without prescribing a single model of care.

At a national level, Canada’s Substance Use and Addictions Program (SUAP) has provided funding for Indigenous-led projects addressing substance-related harms. In 2022, nearly $10 million supported 16 community initiatives nationwide. These projects range from youth prevention and cultural mentorship programs to locally tailored harm reduction services. While federally funded, each project is led by the community it serves, ensuring that solutions reflect local knowledge and priorities.

Policy and research organizations have also contributed to shaping Indigenous perspectives on harm reduction. For example, Stronger Circles and the Canadian Association of People who Use Drugs (CAAN) released a policy brief titled Indigenous Harm Reduction = Reducing the Harms of Colonialism, which underscores that Indigenous harm reduction is not simply about substance use – it is about addressing the ongoing legacies of colonization. This framing situates harm reduction within broader movements for cultural reclamation, health equity, and Indigenous rights.

Together, these examples demonstrate that approaches to substance use within First Nations contexts are not uniform. They are guided by local teachings, shaped by community leadership, and continually evolving to meet the complex realities of Indigenous health and wellbeing.

Conclusion

While the examples of First Nations approaches to harm reduction presented here are not exhaustive, they highlight the diversity of practices and beliefs across communities. Some Nations have adopted harm reduction as part of a broader continuum of care, while others emphasize abstinence, ceremony, or land-based healing as central.

There is no single path toward wellness. What remains consistent is a shared commitment to supporting individuals and communities in ways that are compassionate, culturally grounded, and self-determined.

Share the article