Introduction

Rooster Town was one of several Métis road allowance communities that emerged across the Prairies in the 20th century, following widespread dispossession that forced Métis families from their lands. Though once a vibrant community on the outskirts of Winnipeg’s Fort Rouge neighbourhood, Rooster Town is often missing from mainstream accounts of the city’s history. Its story reflects how colonial policies — scrip, homesteading regulations, and exclusion from land protections — shaped Métis displacement for generations.

Revisiting Rooster Town is important as Canada continues to grapple with development pressures and questions of Indigenous rights. The forces that displaced Métis families a century ago echo in modern policy decisions, including proposed legislation such as Bill C-5. Understanding this history illuminates how “nation-building” projects often advance at the expense of Indigenous communities and why meaningful consent and rights-based approaches are essential.

What is a Road Allowance?

The term road allowance refers to a designated space measured between a paved or unpaved road and the boundary of land sanctioned by entities such as private owners, municipalities, provinces, federal Crown land, or railway corporations. Following the Red River Resistance of 1869-70, many Métis were defrauded or forcibly displaced from their homes and traditional settlements throughout the Red River Valley, mainly within the Red River Valley. These events, combined with the arrival of the Wolseley Expedition and the influx of eastern Canadian settlers, set the stage for what became known as the Road Allowance Period (1900-1960).

Dispossession and the Rise of Road Allowance Communities

As immigrant settlers and European farmers claimed land in the Prairie provinces — the very parcels originally promised to the Métis through scrip — Métis families were forced into parkland and forested regions or settled informally on Crown land. Others built small communities on road allowances: strips of land technically unoccupied but not intended for settlement. This pattern gave rise to the term road allowance people, a defining feature of Métis identity and political history.

Scrip, the Manitoba Act, and the Extinguishment of Métis Title

Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s vision for Western settlement aimed to extinguish Indigenous land rights (Aboriginal Title) to open the region to agricultural and economic development. While the Manitoba Act (1870) constitutionally recognized Métis land rights, the federal government introduced “scrip” to extinguish Métis title, paralleling the use of Treaties with First Nations. Canada’s use of scrip created a system inherently vulnerable to abuse.

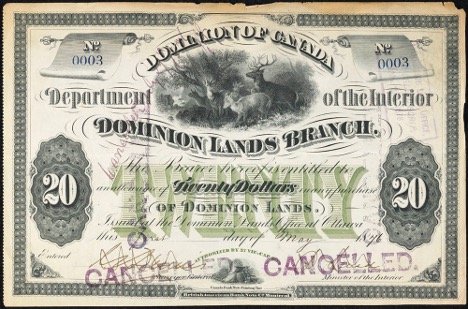

Métis scrip issued for the purchase of Dominion Lands, 1905 (Source: Library and Archives Canada).

The Manitoba Act constitutionally established the legal framework for Métis land title and protection; however, all other land was held by the Dominion of Canada and subject to federal control and regulation. Because Métis land distribution was contingent on the long-delayed Dominion Lands Survey, families waited years before receiving scrip certificates — vouchers redeemable for an individual land grant of approximately 160-240 acres. Scrip was offered to Metis individuals in exchange for their rights, redeemable for money or a homestead. However, the Métis assumed these certificates as protections of their land rights under the Manitoba Act and Riel’s Métis Bill of Rights, but governments and land speculators used scrip as a tool for dispossession. Confusion, inconsistent administration, and outright fraud resulted in the rapid loss of Métis landholdings.

Homesteading Policy and Institutional Exclusion

Growing ambiguity surrounding land allocation intensified through the proliferation of homesteading policies under the Dominion Lands Act of 1872. The Act granted land to capitalists, traders, labourers, municipalities, and religious institutions, including the Hudson’s Bay Company and Transcontinental Railway, as well as the creation of First Nations reserves. However, it offered no statutory protections for Métis families. Overall, the scrip system and homesteading policies created severe instability for the Métis.

“The [Dominion] [Lands] Act was repealed in 1930, when lands and resources were transferred from the federal government to the provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. From 1870 to 1930, roughly 625,000 land patents were issued to homesteaders. As a result, hundreds of thousands of settlers poured into the region.”

Dispossession, Displacement, and Community Formation

Despite Scrip Commissioners travelling to Métis communities to process land entitlement applications, the disorderly conditions created by the settlement of Western Canada facilitated widespread corruption in the scrip system. Métis individuals were impersonated, coerced, underpaid, or misinformed. Many lost their land entirely, leaving Métis people increasingly marginalized, without a recognized land base or legal status.

As a result, dozens of road allowance communities emerged across the Prairies, including in Spring Valley (Saskatchewan), the Qu’Appelle Valley (Saskatchewan), Ste. Madeleine (Manitoba), and Rooster Town, in Winnipeg. These road allowance communities reflected stark poverty: entire families lived in small, one- or two-room, uninsulated homes built from scrap lumber, tarpaper, logs, and salvaged materials. Further poverty was driven by dramatic economic downturns due to depressions, global unrest, war, and racial hiring barriers limiting access to paid labour. In addition, Métis traditional rights, such as farming, bison hunting, and trade, were increasingly restricted under the Indian Act, with seasonal limitations or penalties like fines and incarceration.

Rooster Town Settlement Timeline

1901-1911: Early Growth

- Winnipeg’s rapid population boom increased construction demand, especially in the North End.

- Simultaneously, Métis families began settling on the fringes of Fort Rouge, forming what became known as Rooster Town.

- Industrialization of agriculture displaced many rural Métis farmers who could not afford modern equipment. Unable to compete, they migrated from rural parishes to Winnipeg in search of work.

- The 1901 census recorded 197 Métis residents (or about 42 families) clustered throughout Winnipeg.

- Homes averaged three rooms but lacked sewer lines, electricity, road access, and running water—yet residents still incurred property taxes.

1916-1926: War, Depression, and Decline

- World War I and the subsequent postwar depression created harsh economic conditions and rising living costs.

- As a result of the above and a scarcity of resources, Rooster Town saw a decline in population and growth.

- By 1916, the census estimated the community had 144 residents.

- The 1921 census showed three-quarters of households owned their land, while one-quarter rented. Land was typically city-owned or purchased from real estate companies or private Winnipeg residents.

1931-1946: Relief, Growth, and New Hardship

- The Great Depression deepened poverty and debt across the Prairies.

- The turmoil of the 1930s necessitated government provision of social assistance through Winnipeg’s public welfare department for those registering for relief.

- Rooster Town dwellings experienced staggering unemployment rates (exceeding 25% of residents) and interference from tax collectors and relief officers.

- Many residents were unskilled, and work was informal. Despite hardships, hunting, trapping, gardening, and informal labour remained central parts of community life.

- By the mid-1940s, Rooster Town had grown significantly, redefining its boundaries and increasing connections to suburban development and nearby urban services.

- With approximately 59 households (~250 residents), it began attracting attention from government and social services.

1951-1961: Social Pressure and Erasure

- Post-World War II, socioeconomic mobility for Rooster Town residents was limited; but strong Métis culture and kinship networks created social cohesion, stability, and development.

- Social service agencies and city officials increasingly targeted Rooster Town, often influenced by sensationalized media portrayals in the Winnipeg Free Press and Winnipeg Tribune.

- Newspapers labelled residents as “disruptors” or “convicts,” renewing harmful stereotypes about Indigenous people in urban spaces.

- A 1952 City of Winnipeg housing report from the Committee on Public Health and Welfare noted poor housing conditions and overcrowding, citing “poor housing” within city limits.

- Postwar economic upturn and upward pressure for housing demand led to suburbanization; the drive to develop inexpensive land on the fringes of Fort Rouge was contingent upon developing the Rooster Town land.

- As suburban development expanded — including Grant Park Shopping Centre and Grant Park High School — pressure to clear the land intensified, with city solicitors recommending payment for Rooster Town families to move.

- In 1959, the Winnipeg City Council approved the removal of Rooster Town.

- The Council offered $75 per household, intended to assist with moving costs. However, the grant was conditional: residents were required to vacate their homes by the end of May or receive a reduced amount of $50 by the end of June.

- The city specifically issued eviction notices for sites designated for immediate development, notably the area where the Grant Park High School was planned.

- By 1961, Rooster Town was erased, ending six decades of community history.

Rooster Town and Repeated History: Bill C-5 and ‘Special Economic Zones’

Bill C-5 proposes to expedite the approval and construction of major “nation-building projects,” including railways, ports, pipelines, and other critical infrastructure. The Bill allows the federal Cabinet to designate certain projects as being in the “national interest,” enabling:

- Shortened/fast-tracked environmental and impact assessments.

- Streamlined regulatory processes.

- Approval and review timelines are reduced to two years, with a focus on how to build rather than where to build.

Although framed as a response to economic pressures and trade uncertainty, Indigenous leaders across Canada have warned that the Bill mirrors historical patterns of dispossession, viewing Bill C-5 as a power grab.

Like the development pressures that destroyed Rooster Town, Bill C-5 risks prioritizing economic ambitions over Indigenous consent, land rights, and community wellbeing. It continues a long continuum of Canadian development policy in which Indigenous land is framed as a barrier to progress, echoing the very dynamics that displaced Métis families throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Final Thoughts

The history of Rooster Town is a reminder of both the resilience of the Métis and the vulnerability of communities marginalized within formal governance systems. Even under challenging conditions, Rooster Town thrived through kinship, cultural continuity, and mutual support. Its destruction in the early 1960s, driven by development pressures and discriminatory narratives, reveals how easily Indigenous communities and peoples have been displaced when their presence is seen as inconvenient to settler priorities.

As Canada considers new development frameworks, including Bill C-5, Rooster Town underscores the consequences of making decisions without Indigenous consent. Preventing the repetition of past harms requires centring Indigenous rights, jurisdiction, and community wellbeing in all major projects. Remembering Rooster Town is not only an act of historical recognition but also a call to ensure that future development honours the people and lands that have long shaped what is now known as Canada.

Share the article